Thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS) is a critical condition both in medicine and within the medico-legal setting. TOS is not easy to recognise, diagnose and treat, often resulting in a patient’s prolonged suffering before the condition is finally identified. In fact, the diagnosis of TOS is generally dependent on the clinician’s familiarity with the complexity of TOS, taking into account the symptoms as well as the patient-specific risk factors. TOS patients can be subjected over months or years to unnecessary tests and specialist examinations without a conclusive diagnosis. The treatments offered are often unnecessary, bringing no benefit to patients who frequently develop significant mental health disturbances. With a delayed diagnosis, the patient’s condition may become so severe that a full recovery is unachievable because a sustained TOS can cause irreparable damage to the nerves of the brachial plexus. In compensable circumstances, the condition may also attract a permanent impairment value.

In this newsletter together with Mr Thomas Kossmann, who has himself identified several TOS cases in his medico-legal work, we will provide a brief overview of the pathological characteristics of TOS. In addition, we will present a specific case study to illustrate the roller coaster of an individual who suffered a significant impairment of the function of the upper limb. It was only years later at the medico-legal examination that TOS was finally identified and treated allowing the patient to regain work capacity.

Anatomy

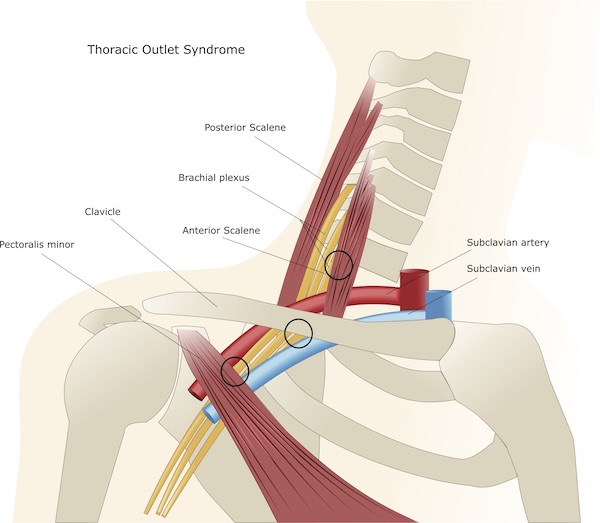

In order to understand this pathology, we provide some anatomical descriptions. The brachial plexus is a bundle of nerves originating from the spinal cord, which exit the vertebrae of the cervico-thoracic spine (C5 to T1) and descending along the body to form the brachial plexus. From here they interchange and extend along the shoulder, the upper arm and forearm distally to the hand and fingers. The main nerves of the shoulder / upper extremities are the axillary nerve, and the median, radial and ulnar nerves.

The artery supplying the upper limb arises from the aorta and is called the subclavian artery. As it descends along the upper limb, the subclavian artery branches into the axillary artery that turns around the humeral head and the deep brachial artery that runs along with the deeper structure of the arm, to then split into the major arteries of the forearm, the radial and ulnar arteries. The main veins of the shoulder, upper arm, elbow and forearm are the cephalic vein, the basilic vein, and the brachial vein, which drain the blood from multiple veins of the hand and forearm.

The thoracic outlet is the anatomical area situated in the lower neck defined as a set of three spaces between the clavicle and the first rib, through which several important neurovascular structures as outlined above.

Pathology: Thoracic Outlet Syndromes

TOS comprises a group of diverse disorders that involve the compression of the nerves, arteries and veins in a region enclosed between the lower neck and the upper chest.

TOS also includes the scalene/scalenus entrapment syndrome caused by the hypertonic anterior scalenus or scalene muscle compressing the brachial plexus and subclavian artery against the first thoracic rib.

The symptoms of TOS are the result of compression to the brachial plexus, the subclavian artery and veins as they go through narrow passageways extending from the base of the neck to the axilla (armpit) and arm.

Different forms of thoracic outlet syndromes

The classification of TOS is based on the pathophysiology of symptoms with subgroups consisting of neurogenic, venous, arterial and non-specific aetiologies.

Neurogenic TOS is the most common type caused by the compression of the brachial plexus, which is characterised by the Gilliatt-Sumner hand, consisting of severe tissue wasting in the base of the thumb. Other symptoms include paraesthesias in form of pins and needles sensation or numbness in the fingers and hand, change in hand colour, hand coldness, or dull aching pain in the neck, shoulder and armpit.

Venous TOS is caused by the compression of the subclavian vein, featuring pallor in the affected arm, which also may be cool to the touch than the healthy arm. Symptoms may also include numbness, tingling, aching, swelling of the extremity and fingers and weakness of the neck or arm.

Arterial TOS is caused by compression of the subclavian artery presenting a weak or absent pulse in the affected arm, change in colour and cold sensitivity in the hands and fingers, swelling, heaviness, paraesthesias and poor blood circulation in the arms, hands, and fingers.

Nonspecific-type TOS is often called disputed TOS because some physicians don’t recognise it, while others believe it’s a common disorder. Patients with TOS have chronic pain in the region of the thoracic outlet that worsens with activity, with the cause of pain remaining elusive.

Causes

Because of the wide range of aetiologies and lack of expert consensus for diagnostic testing, the true incidence of thoracic outlet syndrome is difficult to determine. Several articles report an incidence of 3–80/1000 people.

Neurogenic TOS accounts for over 90% of the cases, followed by venous and arterial aetiologies. Historically, TOS presents with symptom onset between the ages of 20–50 years of age and is more prevalent in women.

Common causes of TOS include physical trauma e.g. car accidents, in particular side impacts or roll-overs, whip-lash injuries, falls, repetitive injuries from work or physical activities (typing, work on assembly line, swimming), congenital anatomical defects (such as having an extra cervical rib or an abnormally tight fibrous band connecting the spine to the rib), poor posture (drooping the shoulders or holding the head in a forward position), pressure on the joints caused by overweight and carrying heavy weights, pregnancy due to joint loosening and even tumours of the superior pulmonary sulcus. However, sometimes it remains difficult to determine the true cause of TOS.

Symptoms

The symptoms vary, depending on which structures are compressed. Generally, during a medical examination, it was observed by Mr Kossmann that TOS causes pain to the neck, chest, shoulder and arm. Patients also complain of headaches/migraine, occipital pain, pain behind one or both eyes, pain in one or both temporo-mandibular joint of the jaw, pain in the area outside of one or both ears, strange sensation in parts of their face, tinnitus, blurry vision and dizziness with or without elevating one or both arms.

When nerves are compressed, signs and symptoms of neurological thoracic outlet syndrome include:

• Muscle wasting in the fleshy base of the thumb (Gilliatt-Sumner hand)

• Numbness or tingling in the arm or fingers

• Pain or aches in the neck, shoulder or hand

• Weakening grip

Symptoms of vascular thoracic outlet syndrome include:

• Hand discolouration of hand (bluish colour)

• Arm pain and swelling (blood clots)

• Blood clot in veins or arteries in the upper body region

• Pallor in one or more fingers or the entire hand

• Weak or no pulse in the affected arm

• Cold fingers, hands or arms

• Arm fatigue with activity

• Numbness or tingling in the fingers

• Weakness of the arm or neck

• A throbbing lump near the collarbone

Complications

Progressive nerve damage is a possible complication if the symptoms do not resolve early. In addition, while surgery may be necessary, it may not eliminate the symptoms.

Diagnostic tests

A variety of clinical tests are employed to provoke the symptoms and diagnose TOS.

Surrender test – The examiner localises the radial pulse of a patient and keeps recording the pulse whilst the patient is elevating the arm. Normally the radial pulse should remain palpable even when the arm is fully elevated. However, in patients with TOS the radial pulse will disappear at some stage during the elevation. When the pulse is no longer felt, most patients complain of tingling and numbness in their fingers. These symptoms can increase when the head is turned to the contralateral side, whilst the patient keeps the arm elevated.

Adson test – The arm is abducted 30° at the shoulder while maximally extended. When extending the neck and turning head towards the shoulder, patient inhales deeply.

Results: Decrease or absence of ipsilateral radial pulse.

Elevated Arm Stress Test (EAST test) or ROOS test (see image above) – Arms are placed in the surrender position with the shoulders abducted to 90° and in external rotation, with elbows flexed to 90°. The patient slowly opens and closes hand for 3 min.

Results: Enhanced pain, paraesthesia, weakness on the affected side.

Upper Limb Tension Test or ELVEY test – Position 1: arms abducted to 90° with elbows flexed; Position 2: active dorsiflexion of both wrists; Position 3: the head is tilted ear to shoulder, in both directions.

Results: Positions 1 and 2 trigger symptoms on the affected side, while position 3 years elicits symptoms on the contralateral side.

Objective tests

Electrodiagnostic test via nerve conduction studies is used for suspected neurogenic TOS. This test may reveal diminished or absent median and ulnar motor response. The test has to be performed with elevated arms, otherwise no pathology will show up.

Imaging is recommended to detect anatomical abnormalities or defects. X-rays of the cervical spine and chest are recommended to localise the cervical ribs or other radiological features potentially responsible for obstruction of vessels or nerves. Conventional arteriography and venography, although not always definitive, are better replaced by ultrasound (usually first choice for high sensitivity/specificity) and CT and MRI scans.

Differential Diagnosis

The diagnosis and treatment of thoracic outlet syndrome and scalenus entrapment syndrome are still controversial, as the symptoms overlap with other pathologies, making TOS difficult to recognise and requiring differential diagnosis to exclude other conditions. These pathologies are rotator cuff injury, cervical disc disorders, fibromyalgia, multiple sclerosis, complex regional pain syndrome, and tumours of the syrinx or spinal cord.

Treatment

Conservative treatment

The key to the treatment of TOSs is early diagnosis, which improves the chance of recovery. Conservative options include physical therapy, lifestyle modification, pain management, anticoagulation and rehabilitation.

Patient education, TOS-specific rehabilitation, and pharmacologic therapies have shown some success. Conservative treatment does not have a proper consensus. Rehabilitation consists of education on postural mechanics, weight control, relaxation techniques, activity modification, and TOS-focused physical therapy. Such an approach can achieve good results over several months of treatment (6 months). Nonoperative management is more indicated in neurogenic TOS whereas in vascular or refractory neurogenic TOS, surgery may be required.

Surgery

Vascular TOS: anticoagulation via catheter-directed thrombolysis and systemic heparin therapy may be first attempted. Surgical candidates should have failed conservative management. Cervical rib (if present) or first rib resection is the main approach aimed at brachial plexus decompression via transaxillary, supraclavicular, and infraclavicular techniques. More recently, alternative minimally invasive techniques have achieved superior outcomes in first rib removal, as both robotic and thoracoscopically assisted approaches minimise brachial plexus manipulation. Following surgical intervention, 95% of patients with neurogenic TOS reported ‘‘excellent’’ results and have no or almost no symptoms anymore.

CASE STUDY OF THORACIC OUTLET SYNDROME

Three months later, based on a CT scan result the patient was diagnosed with inferior capsule injury of the left shoulder with minor changes in the bursa. This was followed by a surgical procedure with subacromial decompression, after which the patient achieved temporary pain relief and functional improvement. Because of her continued neck pain, the patient underwent an MRI investigation of the cervical spine, which only showed a minor disc bulge at C5/C6.

When the patient arrived at Lex Medicus for a consultation two years after the initial accident, she complained of headache and pain behind the eye. Upon surrender test, she felt pins and needles whilst lifting the left arm. These symptoms were recognised as the hallmarks of a thoracic outlet syndrome. The medical history over the past two years showed that the patient had undergone different types of investigations and care, including consultations with an osteopath, Pilates, swimming, and multiple ophthalmologic reviews due to her eye issues. However, none of these specialists identified the pathology. In addition, over the past 6 months, the patient had increasing migraine attacks.

On the recommendation of the Lex Medicus consultant, the patient was referred to a neurosurgeon, experienced in the diagnosis and treatment of TOS, who confirmed the pathology. The suggested treatment with a specialised physiotherapist was unsuccessful and the migraines became more frequent and intense.

The diagnosis of TOS was also confirmed by a neurologist, who, contrary to the neurosurgeon, believed her condition was not the consequence of her work-related accident in the hospital. However, the neurosurgeon maintained in his report: “The headaches described by this patient involving the ipsilateral head, radiating from the occipital to the front region and involving the eye, are absolutely classical of the headaches caused by thoracic outlet syndrome, due to involvement of symptomatic outflow to the head and neck region from the lower trunk of the brachial plexus, which is involved in this condition.”

Also, when the Medical Panel reviewed this case, they confirmed that the patient’s employment was a significant contributing factor to the left shoulder and neck injury and thus the development of TOS.

Eventually, the eye issues became so severe that the patient partially lost vision as well as sensation to the left arm and even to the left leg. The left shoulder dropped, which forced her to place the arm in a collar and cuff. At this point the patient was advised to see a cardiothoracic surgeon who performed a left trans-axillar first rib resection (see picture above), meaning the partial removal of the first rib with access below the armpit. Although surgery had a positive impact on the patient’s migraines, the constant headaches remained, requiring painkillers and making repetitive work with the left arm problematic. The patient also reported difficulties with daily activities such as dressing, doing up zips and washing and brushing hair. The patient eventually returned to work in a part-time capacity.

Five years after the onset of the TOS symptoms, the patient attended an emergency department due to left arm pain, numbness, weakness, nausea, headaches, chest pain to the left side and lethargy. The MRI of the cervical spine and left brachial plexus only showed mild disc desiccation at the C5/6 level, but no other pathology. Later on, the patient was admitted for an overnight stay in the hospital for symptoms to the left arm. In that setting, brain CT scan and cerebral venogram did not reveal any abnormalities.

During a further consultation with a Lex Medicus expert, the patient mentioned that she was no longer depressed but suffered from stress and anxiety. In view of the patient’s previous suicidal thoughts at the peak of the TOS symptoms, this was a clear improvement of her mental state. Due to the continued, albeit milder symptoms, the patient abandoned the former physically-demanding job in the hospital to pick up an administrative role. Unfortunately, despite her young age, the patient continues to present with an impairment as a consequence of her injuries and conditions. It is likely that this impairment is permanent and will continue for the foreseeable future.

Impairment assessment

The impairment assessment of a patient with TOS is a challenge.

Importantly, the symptoms of TOS are equal to a partial brachial plexus lesion.

How to approach the impairment assessment?

The impairment assessment is based on the clinical examination. The evaluation in TOS patients shows that the symptoms appear at a certain degree of flexion of the shoulder joints in the form of a sensory deficit and pain which is the key for the impairment assessment.

Based on this assumption, the impairment assessment begins with Table 11, page 3/48 of the AMA guides 4th Edition. In this table there are descriptions of the sensory deficit or pain, and a range of symptoms from no loss of sensibility / no abnormal sensation/ and no pain, to the worst symptoms in form of decreased sensibility with abnormal sensation and severe pain, which prevents activity and /or major causalgia.

The task is to match the symptoms of the TOS patients with the symptoms described in the Table.

The next step of the assessment is found in Table 14, page 3/52. The impairment is calculated for the right and left extremity, depending on if one or both upper extremities are affected by TOS. The UEI value for each upper extremity separately is then used to calculate the Whole Person Impairment (WPI) according to Table 3, page 3-20 and if required combined.

Practical example

A patient presents with the onset of TOS symptoms at 150° flexion in the affected shoulder joint in form of a sensory deficit and tingling in the fingers. This is the basis for the calculation.

With this assumption, the first step in the impairment assessment is using Table 11, page 3/48. The symptoms of these patients are best matched with grade 3 (Decreased sensibility with or without abnormal sensation or pain, which interferes with activity). The percentage of the sensory deficit is 30%.

Then the second step is found in Table 14, page 3/52. In this case, the sensory nerves of the whole brachial plexus are affected. The calculation is 30% of 100% UEI = 30% UEI of the affected extremity.

The third step is to transform UEI into a WPI. According to Table 3, page 3/20, WPI corresponds to 18% for this extremity.

The same calculation is repeated for the other extremity if symptoms of thoracic outlet syndrome have been detected on the contralateral side as well. Then both values are combined.

Disclaimer: All images and content published in the Lex Medicus, and Lex Medicus Publishing websites are protected by copyright.