Disc herniation of the spine represents a frequent example in compensation cases addressed by personal injury lawyers and insurers such as WorkSafe Victoria and Traffic Accident Commission (TAC). We believe the description of this pathology with a detailed explanation of the treatments provided will be useful to better address a client’s claim.

Disc herniation is highly common in our community, mostly affecting the cervical and lumbar spine. The spectrum of symptoms, diagnostic and treatment modalities varies considerably, thus leading to an array of controversies to address a complex condition. The most common debates include surgery versus conservative treatment, patient’s ability to return to work, and when a claim is presented how to compensate the client in monetary terms.

Spine injuries and degenerative pathologies of the spine present a major health burden to our societies. Back pain is the second leading condition that requires medical attention. Up to 80% of adults will experience at least 1 episode of low back pain during their lifetime, and 5% will have recurrent problems some of which remain chronic. Back pain is the most common reason for work absence and loss of income and productivity, thus representing a significant epidemiologic problem.

According to the WorkSafe Victoria Statistical Summary 2011/12, the number of claims reported for a back injury in the workplace amount to 5517 in the years 2011/12. This number exceeds by far claims for injuries to the shoulder (3277), hand and fingers (3145) and knee (2691). In this report, claims for back injury constitute 19% of all claims to WorkSafe. Although the number of back injuries reported has significantly decreased from 7,670 in 2002/3, this latest figure gives a real perspective to the magnitude of a problem encountered in the workplace, thus having a huge impact in compensation costs. This statistic, however, does not take into account all other back injuries that are not work-related.

Back injuries due to road traffic accidents were 221 in 2014 leading to a total compensation of over AU$20 million in 2014/15 without the inclusion of quadriplegia (approx. AU$40 million) and paraplegia (AU$15 million) (TAC Annual Claim Statistics 2015; https://www.tac.vic.gov.au/about-the-tac/media-room/news-and-events/2015-media-releases/latest-tac-claims-data-reveals-injury-hotspots-in-regional-victoria).

Disc herniation pathology

Herniation of the intervertebral disc – also named disc prolapse, ruptured disc or slipped disc – occurs when the gelatinous content of the disc protrudes towards or outside the rim of the disc.

Anatomy of a healthy vertebra and disc

Disc herniation causes

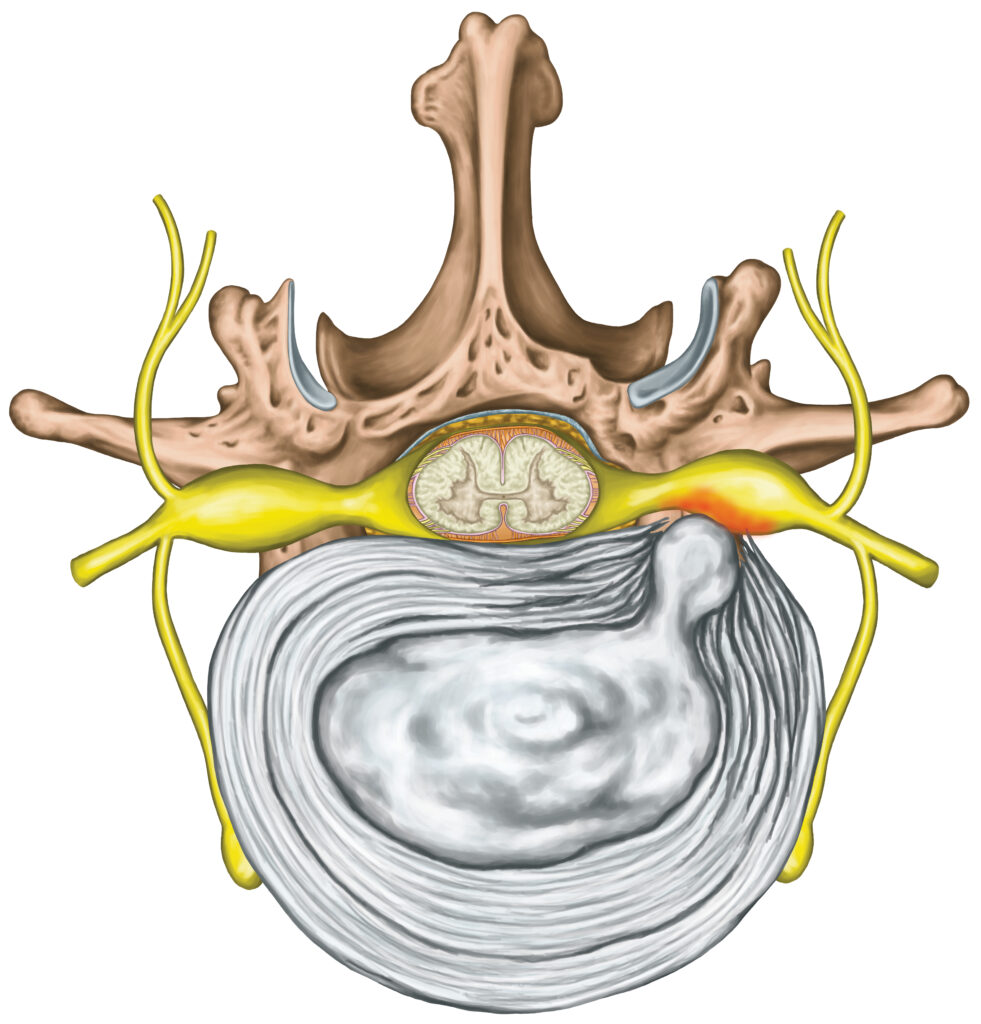

Disc herniation is one of the most frequent causes of back pain mostly affecting the lower spine. The intervertebral disc is a cushion-like structure positioned between the vertebrae to absorb stress to the spine and facilitate movement. The disc comprises a fibrous outer ring, the annulus fibrosis, and a jelly-like material filling the centre of the disc, the nucleus pulposus. The initial stage of the condition involves the herniation of the nucleus pulposus towards the annulus fibrosis. The annulus fibrosis can present one or more tears or a complete rupture causing the total or partial release of the nucleus pulposus into the outer space. This can produce pressure on the spinal cord and nerve roots. Disc herniation causes local inflammation and possible nerve damage resulting in significant pain, clinically known as radiculopathy, and in some cases severe neurological symptoms in form of paresis, e.g. foot drop.

A herniated disc causes pressure on the nerve, pain and neurology

Herniated discs definitions

Herniated discs may be defined as bulges, protrusions, extrusions or sequestrations, depending on the contour of the displaced material, their volume and their distance from the centre of the disc.

Bulge & Protrusion (degeneration): the disc bulges without rupturing the annulus fibrosis.

Prolapse: the nucleus pulposus is displaced to the outermost layers of the annulus fibrosis.

Extrusion: the annulus fibrosis is perforated and the gelatinous material is pushed to the epidural membrane enclosing the spinal cord.

Sequestration (subtype of extrusion): The disc is fragmented and can be found as free-floating material within the spinal canal causing significant pain and neurological symptoms.

Additional classification of disc herniation relies on the type of displaced material (nuclear, cartilaginous, bony, calcified, ossified, collagenous, scarred, desiccated, gaseous or liquid), and whether the material is contained within the intact annulus or uncontained when outside its boundaries. The consequent compromise of the spinal canal by a herniated disc is graded as mild if less than 1/3, moderate if 1/3 to 2/3, and severe if over 2/3 of the spinal canal space is obliterated.

Illustration of the different stages of disc herniation

Disc herniation caused by trauma

Trauma, either single or repeated, is the most common mechanism of disc herniation caused by the rupture of the annulus fibrosus. This leads to the protrusion and/or extrusion of the disc material into the vertebral canal. When the disc has collapsed the space between the vertebrae is reduced. Disc degeneration is often the result of lifestyle activities, work-related and tissue wear and tear. It usually arises in older people due to disc fibrosis and narrowing of the disc space, deterioration of the annulus, sclerosis of the vertebral endplates and presence of bony growths (osteophytes) in the inner space of the vertebrae. The prolapsed disc generates pressure to the nerves and possibly the spinal cord.

A traumatic impact is the most frequent cause of disc herniation

Risk and genetic factors of disc herniation

Disc herniation is most common in men between 30 and 50 years of age and in all ageing individuals.

These are the main risk factors:

- Overweight/obesity increases pressure on the spine and intervertebral discs, particularly in the lumbar section.

- Smoking reduces peripheral blood circulation and diminishes the blood supply to the disc, facilitating its degeneration.

- Genetic factors cause anatomical changes in the vertebral endplate diminishing nutrition of the disc, and predisposing to subsequent pathological alterations.

Poor physical fitness including:

- Sedentary lifestyle weakening the supporting spinal muscles

- Frequent driving

- Inadequate sporting technique

- Improper posture when weight lifting or sitting at a desk

- Sudden pressure to the spine

- Repetitive strenuous activities in labourers performing heavy physical work.

Frequent bending and carrying heavy weights is a significant risk factor for disc herniation

Disc herniation symptoms

Symptoms of a herniated disc differ depending on the section of the spine where it occurs. Local pain is the most frequent sign. It can be acute or increase gradually extending to the limbs (e.g. disc herniation to the lower spine causes pain to the leg and foot known as sciatica). Below is a list of symptoms, which can present either alone or in combination for herniated discs of the cervical and thoracic/lumbar spine as they are more frequently affected.

- Cervical spine

- Neck pain

- Burning pain in the shoulders, neck and arm

- Muscle pain between neck and shoulder (trapezius muscles)

- Shooting pain extending to the arms

- Headaches

- Weakness in one arm

- Tingling (“pins-and-needles” sensation)

- Numbness in one arm

- Loss of bladder or bowel control in serious pathology

- Thoracic / Lumbar spine

- Thoracic / Lower back pain

- Burning pain in the buttock, thigh, calf and foot

- Shooting pain to one or both legs

- Weakness in one or both legs

- Tingling (“pins-and-needles” sensation)

- Numbness in one or both legs

- Loss of bladder or bowel control in severe cases

Pain to the area of the spine affected by a disc herniation is the main symptom

Examination of disc herniation

During clinical investigation, the doctor records the medical history including recent and past injuries, lifestyle, physical and neurological symptoms. For a suspected disc herniation, the examiner carries out a neurological assessment using the straight leg tests, Lasegue and Bragrad tests.

Radiological imaging in particular MRI allows to visualise at best the discs and the spinal cord. MRI is also more sensitive to identify minor fractures, which can be difficult to see on X-rays. Often CT scans and X-rays are also used as a first diagnostic tool.

Myelography with CT scan was used frequently previously to determine the reduction in the diameter of the spinal canal (stenosis) following disc herniation but has been replaced by MRI.

Discography is a functional test consisting of the injection of a contrast solution into the vertebrae, which may trigger pain similar to a disc herniation. This is followed by a CT scan to pinpoint the exact location and define the classification of disc herniation. However, discography is not considered sufficiently specific and is hardly used nowadays.

To exclude the contribution of other pathologies such as cancerous metastases growth to the spine, diabetes, infections and multiple myeloma, laboratory tests are useful for cancer biomarkers (e.g. PSA, prostate-specific antigen), diabetes (glucose level), erythrocytes sedimentation rate (ESR) and multiple myeloma (Bence Jones proteins in urine).

MRI of a patient with multilevel disc herniation to the cervical spine. Note the compression on the spinal cord

Treatment of disc herniation

In the absence of severe neurological symptoms, conservative treatment of the herniated disc is recommended. This includes pain relief medications together with a short period of bed rest, avoiding prolonged sitting, bending, weight lifting and any activity, which puts pressure to the spine. The use of oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) is prescribed to dampen local inflammation.

Epidural injection of more powerful steroids is advised if symptoms are more severe. Other conservative measures include the application of hot or cold packs, massage, myotherapy and acupuncture. Once the acute phase has subsided physical therapy can begin to gradually strengthen the muscles of the spine and abdomen to support the spine and alleviate pressure on the disc.

A cold pack helps relieve pain and inflammation

Surgery on disc herniation

Surgery is only recommended in a small population of patients with disc herniation when conservative treatment fails to resolve ongoing pain or in case of aggravation of neurological symptoms. Surgery is usually performed following anti-inflammatory therapy.

Microdiscectomy is the most frequent operation to the lumbar spine and consists in the removal of the herniated portion of the disc and any disc fragments that compress the spinal nerves.

Laminectomy may be applied to remove the vertebral lamina for better access to the disc. Microdiscectomy utilises a special microscope to view the spinal canal, the disc and local nerves. The combination of a small incision and a microscope reduces the risk of damaging the nerves and surrounding tissue.

Spinal fusion is a more extensive surgical procedure whereby two or more vertebral bodies, separated by the pathological disc(s), are fused together with metal implants filled with bone replacement material or allograft from a donor bone. This surgery reduces pain but limits the flexibility of the spine, as the fused vertebrae become a single bone. Numerous surgical approaches are available for spinal fusion and mostly depend on the location of the access to the spine:

- Posterior (from the back)

- Lateral

- Anterior (from the ribcage or abdomen)

Posterior lumbar interbody fusion (PLIF)

Posterior lumbar interbody fusion is the welding of two or more vertebrae via an opening in the back of the spine. Following a midline incision of the skin along the spine and the separation of the muscles, a laminectomy is performed to create space to reach the disc. The nerves are pushed carefully to the side. The disc is resected and replaced with a spacer or cage that is introduced between the vertebrae. The cage is filled with bone graft prior to implantation. To finally stabilise the vertebrae, screws are inserted into the pedicles of the upper and lower vertebrae and then connected with bars or plates.

Transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (TLIF)

Transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion is a variation of PLIF in which the surgeon creates an opening to the lateral side of the spine. This prevents damage to the muscles and excessive displacement of the nerve roots. This technique also permits to better decompress the nerve roots, so-called rhizolysis, by excising the facet joints as well as facilitating the removal of the degenerated disc. TLIF is specifically indicated for recurrent disc herniation and foraminal stenosis (reduction of the space of the spinal cord canal).

Anterior lumbar interbody fusion (ALIF)

Anterior lumbar interbody fusion is achieved by accessing the spine from the abdomen (laparotomy) or through the side of the abdomen (lumbotomy). These approaches reduce the risk of damaging the nerves but require caution to avoid injuries to the vessels, including the aorta, the intestine or other organs (spleen). Following the removal of the disc(s) the space between the vertebrae is filled with bone graft, metal or plastic spacer. Frequent is the use of a metal cage, filled with bone graft. Subsequently, metal rods in combination with plates and screws are placed posteriorly to fuse the adjacent vertebrae.

Bone graft

To accelerate bone healing and improve spine stability, various types of material are grafted following discectomy. Grafts include autologous (patient’s own bone) or heterologous (cadaver) bone, cement and other biological substances. Traditionally autologous bone graft is taken from the iliac crest of the pelvis and requires an additional surgery. Demineralised bone matrices (DBMs) are obtained from heterologous bone following the removal of calcium. They consist of gels rich in proteins that stimulate bone repair. Ceramics are synthetic calcium/phosphate materials with a consistency similar to bone. Bone morphogenic proteins are growth factors with a potent stimulating activity for bone formation.

Artificial disc replacement in the lumbar spine

More recently intervertebral disc replacement surgery has become popular in selected patients excluding those with more than two pathological discs, obesity, previous spine surgery, damage to vertebral facet joint, nerve injury and scoliosis. Artificial discs are mechanical devices of different shape used to replace the degenerated intervertebral disc. Materials include metals (titanium alloy, cobalt chromium) and medical-grade plastic (polyethylene) often used in combination. This technology has been available in Europe, the US and Australia for over a decade with ongoing development. The artificial disc is inserted in the lumbar spine with an anterior surgical approach from the abdomen. The day after surgery the patient is encouraged to walk but avoid extension of the spine. Pain improvement is achieved weeks to months post-surgery but may persist for longer.

Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF)

Disc herniation at the cervical spine creates a strong pressure on the nerves of the neck possibly causing severe neurological symptoms. If conservative treatment is unsuccessful, surgery aims at decompressing the pinched nerves by removing the herniated disc, the bone fragments and possibly growing soft tissue (e.g. cancerous metastases). Additional fusion and disc replacement can be carried out in combination with discectomy. These methods can be applied to diverse pathologies of the neck such as fracture, cervical radiculopathy and instability. Anterior cervical discectomy followed by intervertebral fusion is the most frequent type of surgery for the pathology of cervical discs. The cervical spine is accessed via an incision to the frontal side of the neck, parallel to the spine. Once the herniated or degenerated disc has been removed the surgeon inserts the replacement material to obtain a normal anatomical distance and fuse the vertebrae above and below the pathological disc. This includes a cage filled with autologous (iliac rest) or heterologous bone graft. Fusion of two or more vertebrae can be achieved and in addition plates and screws are often used in multilevel fusions.

Posterior cervical lamino-foraminotomy

Lamino-foraminotomy denotes a small laminectomy with the surgical opening of the foramen (or foraminotomy from which the nerves exit the spinal cord. In this surgery, the cervical spine is accessed from the posterior side of the neck. An incision of approximately 4-5 cm is done on the midline along the spine and the muscles and nerves are gently pushed to the side. The lamina of the vertebrae is excised to release the pressure to the nerve roots. Lamino-foraminotomy may occur without discectomy or intervertebral fusion. This facilitates recovery after surgery.

Minimal/Less Invasive Spine Surgery (MISS/LISS)

Minimal or less invasive spine surgery was developed in the 1990s as an alternative to open surgery to diminish damage to the muscles surrounding the column and decrease the incision size. This technique reduces bleeding, patients’ length of stay in hospital and facilitates recovery. MISS comprises a number of techniques usually performed by experienced surgeons who rely on sophisticated tools. Through a small incision, the surgeon inserts a retractor to move aside the soft tissues and reach the spine. Surgical instruments are long and fine, specially made to fit into the retractor. Using this canal, the surgeon extracts fragments of the injured disc or bone, inserts implants and performs the vertebral fusion. Due to the limited view of the surgical area, a fluoroscope is used to shoot real-time X-rays of the spine, which are displayed on a screen. A microscope is often used to magnify the images of the operating field. When microdiscectomy has been completed the retractor is removed and the muscles allowed to return to their position. MISS is applied to a number of spine procedures in modified forms, including discectomy, lumbar or thoracic spine fusion and reconstruction of the vertebrae following trauma or neoplastic/metastatic growth.

Minimal Invasive Spinal Surgery requires a small incision

Rehabilitation of disc hernia

Rehabilitation during conservative treatment of a disc hernia includes:

- Massage / soft tissue manipulation

- Ultrasound

- Postural taping and postural support (cushions) to maintain optimal position of the shoulders, neck and lumbar spine and encourage alignment of the spine to avoid further damage and recurrent disc prolapse

- Spinal traction

- Cervical collar

- Dry needling

- Physical exercises (e.g. clinical Pilates) to reposition the disc, improve strength, core stability, flexibility and posture

- Education on daily activity modification

- Ergonomic advice on sitting, bending, carrying weights

- Gradual return to strenuous activity program

Post-surgery recovery and rehabilitation

The hospital stay following PLIF, TLIF, ALIF and ACDF is normally quite short (a few days) or even just a day. Following discectomy of the cervical spine, without bone fusion, a neck brace is worn for months to allow bone healing. In the case of fusion with metal instrumentation, the stability of the spine is such that the use of braces is not necessary. The patient can resume normal activities paying attention to not over-stretch or add pressure to the spine. Rehabilitation usually commences a month post-surgery with a gradual step exercise supported by anti-inflammatory treatment. General fitness condition is provided with walking and cycling followed by specific exercises to strengthen the muscles of the cervical and thoracic spine. A specialised physiotherapist will instruct the patient on how to modify daily activities to prevent excessive pressure on the operated vertebrae.

MISS reduces significantly the hospital stay and time of recovery. After surgery patients are rarely admitted to the ICU and remain in the hospital for maximum a week if no complications arise. By preserving the integrity of the spinal muscles and other soft tissues, pain is minimised. Physical therapy can begin sooner accelerating the overall wellbeing of the patient. With spinal fusion, the patient may require longer recovery before commencing strenuous physical activity. It is paramount to maintain a good alignment of the spine for a few months until the vertebrae have healed. Walking and other moderate activities are permitted.

Massage therapy

Prevention of spinal disc herniation

Changes in lifestyle and patients’ technique during physical activity are essential to prevent spinal disc herniation. Firstly, maintenance of physical condition will strengthen the muscles of the spine and alleviate the pressure to the vertebrae, discs and ligaments. Sitting, weight lifting, bending and twisting need to be performed with a correct posture (e.g. by keeping the spine straight and knees bent). Avoiding heavyweights, carrying heavy bags, losing excess weight, and quitting smoking are recommended to improve the health of the spine and prevent recurrent problems.

A correct posture with a mild back exercise is critical to prevent a disc herniation