Death is inevitable, but there are ways we can possibly delay death by abiding to a healthy lifestyle which includes a sensible diet, physical exercise, and regular check-ups with the doctor.

The death of Shane Warne caused by a heart attack is a sad reminder of how critical it is to listen to our bodies when they give signs of ongoing unhealthy processes. Warne’s sudden death at just 52 years is an actual alarm bell, particularly for men who notoriously tend to disregard bodily symptoms and are reluctant to speak about them to friends, let alone their GPs.

Men account for the vast majority of deaths before their 65th birthday. Apart from heart disease, the principal cause of death in men, cancer represents the second prominent pathology leading to early death. Although cancer mortality has dropped in men more than women between 1989 and 2021, men still resist participation in screening programs such as those for bowel cancer. Men also die disproportionately from violence and suicide compared to women.

GP visits and regular health check-ups are less frequent in men

A recent statistic speaks clear: men seek out medical help a lot less than women, a problem that plays a significant role on their health and longevity. Male patients reported less than half of GP visits: 43% in 2015–16 compared to 57% for women. In addition, men received approximately 14 medical services compared to 19.5 in women in 2018–19.

A survey issued by the Cleveland Clinic in the US proved that men are not talking about their health with one another, unless it’s to brag about “hero injuries” like the broken arm from a bike flip gone wrong or the stitches from a carpentry close call. Men are much more likely to discuss current affairs (36%), sport (32%) and their job (32%) than their health (7%) with their male friends.

Over the last decade a growing body of research associated men’s reluctance to seek help with adherence to traditional masculine models (e.g. stoicism). Why? It has been proposed that masculinity ideologies, norms, and gender roles play a part in discouraging men’s help-seeking. Additionally, factors such as socio-economic status, access to and cost of health services, age, level of education and marital status have all been associated with differences in the utilisation of medical care. Negative attitudes to help-seeking are particularly relevant in the context of mental health, which is a topic worth another article.

A few years back, a study utilising a cohort of men from the Australian Longitudinal Study on Male Health, aimed to identify the socio-demographic and lifestyle factors associated with the utilisation of healthcare in men. The research analysed a range of health outcomes, health behaviours and related risk factors, including social determinants of 15,988 Australian males between 10 and 55 years, of whom 60% were living in metropolitan areas and the remaining in regional areas. The findings of the study are the following:

- Although 81% of men saw a GP in the 12 months prior, the majority of them (61%) did not engage in regular health check-up visits.

- The proportion of men having regular health check-ups is much lower than the proportion of men visiting a GP in the past.

- The likelihood of visiting a GP increased with growing age but diminished with remoteness of residence.

- Older men, smokers and those who rate their health as excellent were less likely to visit a GP in the last 12 months. Conversely, those with co-morbidities or taking daily pain medication were more likely to have seen a GP and engage in more frequent health check-ups.

- The chance of a regular health check increased with obesity but, surprisingly, decreased with harmful levels of alcohol consumption.

The study suggests that men see a GP only as needed (e.g., for acute illness or injury) and may not plan their visit on a regular basis. Thus, circumstantial factors are of higher relevance in deciding on whether or not to see a GP, instead of facing a regular medical consultation to allow for disease prevention, early diagnosis and swift medical intervention – all of which would reduce the burden to the healthcare system when the patient’s disease is advanced and possibly irreversible.

Men’s vs women’s health

On average, men’s life span is five years shorter than women. Many aliments have been recognised with the most prevalent being cardiovascular diseases, testicular cancer (the most common cancer in young males) and prostate cancer, which affects over 10 million men globally. Mental health is also a major burden in men, representing three quarters of all suicides in Australia.

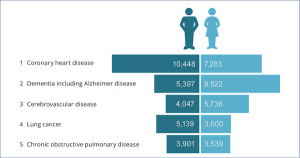

Men’s health is a huge topic. Cardiovascular conditions more than others are a grave problem, being the number one cause of death in men compared to their sex counterparts. Coronary heart disease takes more than 17,000 Australian lives each year (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2019), with the majority of them dying or being hospitalised from it. In 2019 over 10,400 men died from this compared to 7,280 women. More women instead died of dementia (e.g. Alzheimer’s disease; 9,522), and cerebrovascular disease (e.g. stroke; 5,736). Other relevant prominent causes of death in men are lung cancer (5,139), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (3,900), prostate cancer (3,580), colorectal cancer (2,856), and diabetes (2,700).

What can men (and women) do to prevent a sudden heart attack and live a longer, healthy life?

In a recent interview, Dr Billy Stoupas from the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners said, “ignoring niggling chest pain that comes on and off every now and then, and just thinking that it’s nothing to worry about, can have negative outcomes because it can be a sign of heart disease, which can be managed to prevent a full heart attack from occurring”.

Men (and women) should take better care of their heart. A consultation for the heart health check with a GP will:

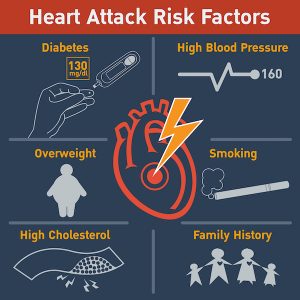

- Ascertain heart disease risk factors including high blood pressure, elevated cholesterol levels and blood sugar.

- Discuss health history and lifestyle concerning diet, physical activity, consumption of alcohol and smoking tobacco, body weight and family history of heart disease.

- Determining the level of risk (low to moderate) of having a heart attack or stroke in the next five years.

- Providing prescription of medications (for high blood pressure and high cholesterol), improving lifestyle habits, and referring to other specialists.

These are the recommended antidotes for a healthy heart:

- Physical exercise. Sitting is the new smoking. A sedentary lifestyle is hugely detrimental to the heart. Four out five Australians do not practice enough physical activity. This is responsible for 11% of the burden of cardiovascular disease.

- Healthy diet. Beer belly is dangerous for the heart. It doesn’t only occur from drinking too much beer or other alcoholic beverages, but also from eating the wrong foods, and those with excessive calories. It is known that visceral fat accumulating around the abdominal organs correlates with cardiovascular disease, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, high cholesterol, fatty liver disease and higher mortality. A poor diet is the second highest risk factor for developing heart disease. How can a change of diet help?

- Reduce salt intake. Australians have approximately 9 grams of salt per day. Salt increases blood pressure and hardens the blood vessels, which adds stress to the heart, our blood pumping machine. Avoid foods like chips, crackers, sauces, processed meats, dips, and baked goods.

- Limit red meats. The Heart Foundation recommends for us to eat less than 350g of unprocessed red meat (beef, pork or lamb) per week, which translates into 1 to 3 lean red meat-based meals each week.

- Plenty of vegetables! A healthy daily diet should be enriched with vegetables, wholegrains, and vegetable oils (olive, canola, sunflower, peanut and soybean oil).

- Healthy foods. Replace animal saturated fats with vegetable oils, fish and seafood, fruit, wholegrain cereals and legumes (chickpeas, beans and lentils). Reduce servings of animal-based products, such as milk, cheese, yoghurt, eggs, poultry and lean meat.

- Blood pressure. A regular check-up of blood pressure from a young age (18 years) and especially with increasing age (from 45 years) is critical, as often high blood pressure does not produce any symptoms. A healthy diet and exercise help manage high blood pressure.

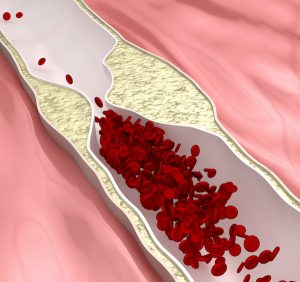

- Lower blood cholesterol. Elevated levels of ‘bad cholesterol’ (Low-Density Lipoprotein or LDL cholesterol) can lead to heart disease because LDL cholesterol sticks to the artery walls, forming dangerous plaques. This build-up can reduce or even block the artery lumen and increase the risk of heart attack or stroke when a plaque dislodges from the vessel wall. High cholesterol can be managed by avoiding foods rich in saturated fats. Also, consumption of nuts, avocados and vegetable oils, eating a healthy diet and taking cholesterol lowering drugs called statins can make a substantial difference in reducing the risk of heart disorders.

How to diagnose heart diseases

The diagnosis of heart disease involves a number of tests aiming to assess the health of the heart itself and the arteries, particularly the coronary arteries.

Coronary computed tomography angiogram (CCTA) is a type of computer tomogram used for the diagnosis of coronary artery disease by providing a 3D image of the heart ventricles and atriums and the coronary arteries.

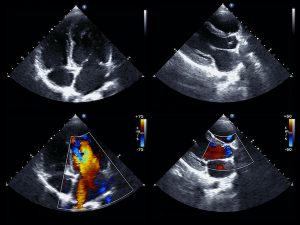

Echocardiogram (heart ultrasound) is usually a non-invasive test employing a probe placed on the chest and sometimes through the oesophagus. With the images generated the specialist can visualise the function of the heart while pumping blood as well as the health of the valves. It can be done straight after a strenuous exercise to visualise the supply of blood to the heart through the coronary arteries.

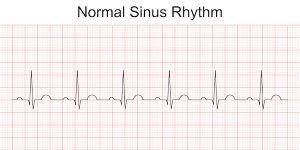

Electrocardiogram (ECG). The ECG records the transmission of the heart’s electrical impulse. This test is useful to determine changes in the heart rhythm (arrythmia) or the diagnosis of heart attack.

Electrophysiology studies. This is an alternative test for the diagnosis of arrythmias. It requires the insertion of a catheter through the leg vein reaching the heart to record electrical activity in response to various stimuli, which allows distinguishment of different types of arrythmias.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) generates detailed images of the functioning heart and can be done with or without contrast dyes for the visualisation of the heart structure and the health of the coronary arteries.

Stress tests involve an exercise stress test such as the ECG while exercising on a treadmill. Alternatively, a stress echocardiogram (stress echo) is used with a tracer injected in the blood stream to detect the heart chambers and valves, as well as the structural changes during the heartbeat. A nuclear cardiac stress test employs the injection of a radioactive substance (tracer) in the bloodstream which releases energy once it reaches the heart. This radiation is captured by a camera, providing images that allow the specialist to quantify the amount of blood flow during rest or under physical stress.

The management of a diagnosed heart disease

The management of heart disease comprises different approaches, depending on whether a heart attack is in action or whether atherosclerosis has been identified in the coronary arteries requiring interventions such as the insertion of a stent or angioplasty. Below is a selection of the main approaches available.

Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation – CPR

Everyone should be trained to perform CPR in case a family member or a colleague is experiencing a heart attack. At Lex Medicus we proudly run such emergency courses every year to prepare our staff for that occurrence. Firstly, the specific symptoms have to be recognised (chest discomfort, pain from chest to upper body e.g. arms, back, neck, stomach, jaw, shortness of breath, etc). At this stage, immediately call the emergency services (000). While waiting for an ambulance, perform CPR (if qualified) through manual chest compression following a specific pattern, at times accompanied by mouth to mouth respiration. If available, a defibrillator (also called AED or Automated External Defibrillator), can be used to address a ventricular fibrillation, a disturbance of the electrical rhythm – often the cause of heart arrest – through a shock delivered by the device through the chest wall to the heart. Nowadays such life-saving devices can be easily used by non-medical people.

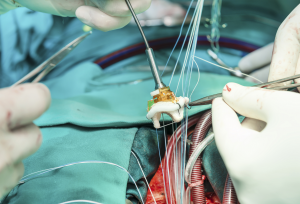

Stents

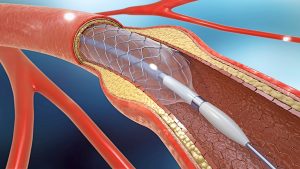

A stent is a small expandable tube traditionally made of a metal mesh that is surgically inserted into the coronary arteries that have narrowed due to the build-up of plaques. More recently, metal stents have been coated with drugs (drug-eluting stents) to prevent re-narrowing of the arteries, which occurs in a quarter of patients. Such interventions reduce chest pain and help prevent a heart attack. This procedure is named angioplasty. Following angioplasty, patients take low dose aspirin or other blood thinning drugs to prevent clot formation.

Balloon angioplasty

This is an alternative procedure consisting of a catheter with a balloon ending inserted through an artery at the groin or arm. Once the coronary artery is reached the balloon is inflated to expand the artery and restore blood flow and removed afterwards. Unfortunately, 30% of the treated arteries become narrow again after this procedure.

Heart bypass surgery

Also known as coronary artery bypass grafting, heart bypass surgery is a very successful approach to restore blood flow when one or more coronary arteries are narrowed or blocked by grafting a blood vessel from another part of the body to restore blood flow to the heart. This is an open-heart surgery, which if accompanied by a healthy diet, exercise and medications can prevent symptoms for a decade or longer.

Valve repair and replacement

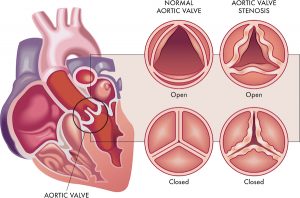

In total we have four valves in the heart, two of which separate the heart chambers, ventricles and atriums (tricuspid and mitral valves), and two valves that separate the heart from the aorta and the pulmonary arteries (aortic and pulmonic arteries). They ensure the correct directional blood flow between these compartments.

Valvular stenosis. All four valves can become stenosed when the opening and closing is not functioning well due to the stiffening of the valve. Valvular stenosis can lead to heart failure due to the stress of the heart to pump blood through.

Valvular insufficiency occurs when the valve does not close completely, allowing some blood to flow backwards. This is also called valve regurgitation and can affect all four valves. Valve disease can be congenital or acquired due to infections or endocarditis.

The treatment of valvular insufficiency can involve the administration of drugs (diuretics, anti-rhythmic drugs, high blood pressure drugs, and anti-coagulants).

Valve surgery is used to repair or replace the heart valve using an artificial valve made of two carbon leaflets and a ring covered by polyester knit fabric. A biological valve is made of human or animal (cow, pig) tissue often associated with artificial parts as a support to the tissue. Other techniques include a homograft (a valve donated from a cadaver) or a non-surgical procedure like a percutaneous balloon valvuloplasty to open the stenotic valve.

Cardioversion

When medications do not work, a heart arrythmia or atrial fibrillation can be treated with a procedure called cardioversion to restore a normal heartbeat and prevent a heart attack and stroke. This technique utilises a device to send electrical energy to the heart. Two options are available: chemical cardioversion using medications, and electrical cardioversion, which gives an electrical shock to regulate the heartbeat using paddles.

Pacemaker

This is a small device implanted under the skin of the chest with the purpose of sending electrical impulses to the heart to maintain a regular heart rate and rhythm. It is applied to people who have had episodes of fainting (syncope), congestive heart failure, bradyarrhythmia (slow heart rhythm) and heart failure. In adult patients the endocardial approach is used whereby the lead of the device under the skin is inserted through the vein and guided into the heart. In children the epicardial approach is used more often to attach one lead to the heart and the other end to the pulse generator under the skin in the abdomen.

Conclusion

I hope this brief overview on men’s health and heart disease has provided valuable information on how to care and prevent irreversible heart disease. Despite the inevitable risk the genetic make-up may bring, particularly with the familiar history of heart disease, and when becoming older, we have the opportunity to monitoring and potentially averting a heart attack. Preventative cardiology has done mammoth steps in determining the probability of heart disease and thus offer medical treatment to those individuals who carry the risks. This article is specifically addressed to men as their occurrence of cardiac problems is higher than women and also because their compliance to routine health checks is low. As you service your car yearly, please be remember to check your health as well, particularly when the years go by.