Everyone would have heard by now of the medical complications many women have endured following reconstructive pelvic surgery performed with the implantation of artificial mesh devices. In women, these surgeries are offered to fix two major problems, urinary stress incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse.

Stress incontinence is a condition causing urine to leak from the bladder during impact activities such as running and jumping, or when sneezing and coughing. The problem is common in women after childbirth and menopause. Around 20% of women suffer from this condition in their daily lives.

Based on clinical studies, it appears that mesh surgery to address stress incontinence has a low complication rate compared to their use in pelvic organ prolapse surgery, which is reported to cause a larger incidence of issues, some of which are severely debilitating.

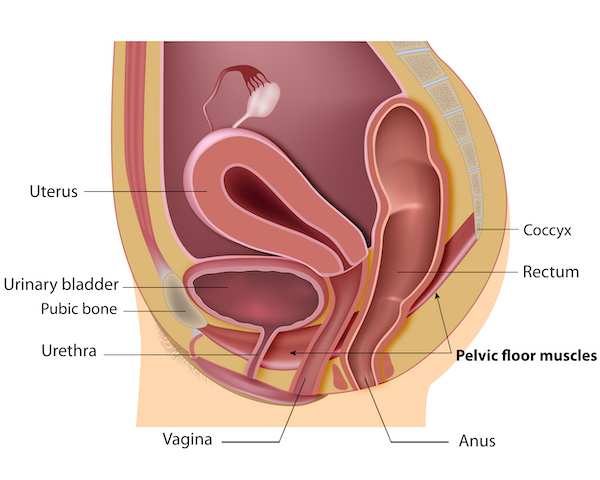

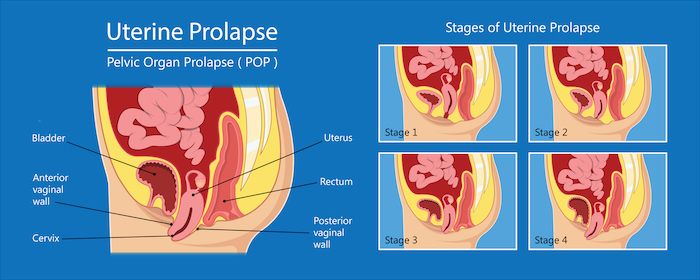

Pelvic organ prolapse is common in women following childbirth and particularly in women who had children later in life. The organs involved, the bladder, rectum and uterus tend to drop thus destabilising the pelvic anatomical organisation. This organ sagging results from the weakening or a traumatic damage (often occurring with childbirth) of the pelvic floor muscles, the ligaments and tissues that hold the organs in place. With the lack of hormones during menopause the pelvic muscles become weak and loose elasticity. Being overweight and having a family history are also risk factors for pelvic organ prolapse.

Treatment of stress incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse

Not all cases of prolapse and incontinence are repaired surgically or using a mesh. The initial treatment is usually conservative involving pelvic floor strengthening by exercise with the assistance of a physiotherapist, electrical stimulation, bladder training, vaginal pessary (a ring-like device inserted in the vagina to support the pelvic organs reducing descent and/or stress urinary incontinence), lifestyle changes (weight loss, avoiding heavy lifting, etc) and use of absorbents.

When the conservative measures do not provide any relief, a woman may be offered surgical intervention. Traditional reconstructive surgical procedures use the patients’ own tissues or tissues obtained from other sources to repair the prolapse, as well as colposuspension performed with either open or laparoscopic approach and bulking agents injected in the urethra.

What is a mesh?

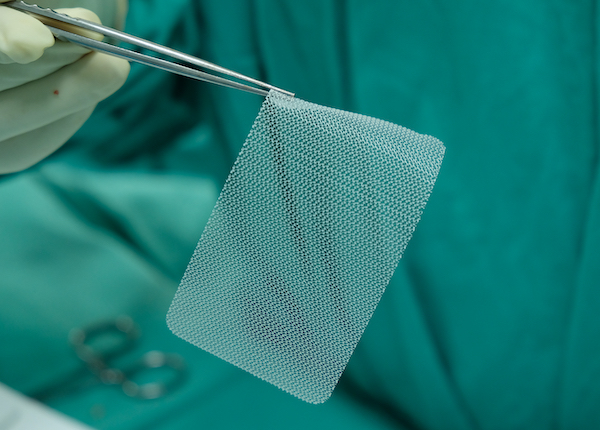

The mesh is a net-like implant. It can have different forms including a “sling”, “tape”, “ribbon”, “mesh” and “hammock”. The aim of the mesh is to give permanent support to the weakened organs and to repair the damaged tissue.

There are different mesh materials that are used as reinforcement for soft tissues and bones. They are predominantly made of synthetic polymers or biopolymers. They include:

- Non-absorbable synthetic polymers (polypropylene)

- Absorbable synthetic polymers (polyglycolic acid or polycaprolactone)

- Biologic (acellular collagen sourced from cows or pigs)

- Composite (a combination of any of the materials above).

Most surgical mesh devices used for female pelvic reconstructive surgery are made of non-absorbable synthetic polypropylene, which is a rather rigid material.

In search for alternative materials more suitable for pelvic surgery, a recent study conducted by the University of Sheffield has developed a softer and more elastic mesh made of polyurethane, which is more appropriate for use in the pelvic floor and one that releases oestrogen into the surrounding tissue to form new blood vessels and ultimately speed up the healing process. Trials will be required to test their suitability.

How is the mesh used in pelvic reconstruction?

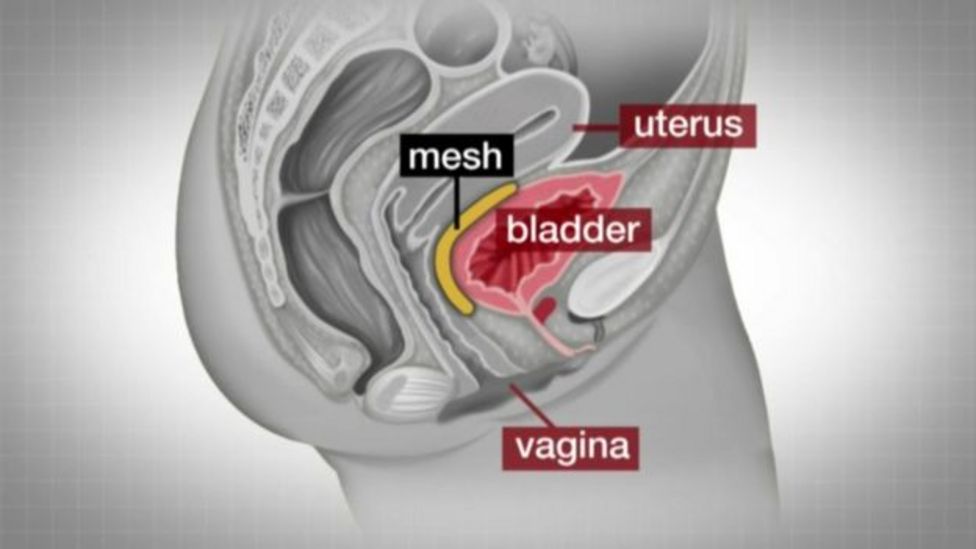

There are three main procedures performed using surgical mesh:

- Transvaginal insertion of mesh to treat pelvic organ prolapse

- Transabdominal insertion of mesh to treat pelvic organ prolapse

- Mesh sling to treat stress urinary incontinence: A multi-incision sling procedure may be performed in which three incisions (cuts) are made

In the retropubic procedure, two very small incisions are made above the pubic bone and a third incision is made in the vagina.

In the transobturator procedure, two very small incisions are made in the groin and thigh, and one is made in the vagina.

A mini-sling procedure, with the insertion of a shorter piece of surgical mesh, which requires only one incision.

Numbers of pelvic mesh surgeries worldwide

In the UK, one out of three prolapse surgeries and 80% of incontinence surgeries were done using transvaginal mesh. While the exact number of women receiving mesh surgery is not clear, in the UK it is estimated that the procedure was performed on about 17,000 women per year suffering stress incontinence.

The number of vaginal mesh implants used for prolapse peaked around 2009 with 3,200 implants, which dropped gradually to about 2,000 per year.

According to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), 300,000 women in the US underwent surgical procedures for prolapse each year and approximately 260,000 underwent surgical procedures to repair stress incontinence.

The equivalent statistics are difficult to access in Australia, as these surgeries are commonly classified as “vaginal repair”, including a variety of procedures that do not involve a mesh. In addition, there is no registry that records specifically these types of surgeries. It is however known that several thousands of Australian women have been implanted with pelvic mesh devices according to the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA).

Which are the complications caused by pelvic mesh surgery?

Initially, the implantation of mesh products was only used to treat urinary stress incontinence via a mid-urethral sling by implanting a ‘very small’ piece of mesh, that was fixated at two points only. This approach had a low complication rate at around 2–3%.

With the excitement of this successful outcome, the use of mesh products was expanded to include the surgery to treat pelvic organ prolapse. This surgery however, required much larger pieces of mesh and multiple points of attachment that significantly increased the risk of complications.

Despite this heightened risk, the meshes were approved for use and actively promoted to surgeons, leading to millions of prolapse treatment surgeries not just in Australia but across the world.

The meshes have caused severe complications for the women involving chronic inflammation, leading to pain and scar tissue formation around the implant. For these women, the complications can be serious, debilitating and life-altering. You can find a patient case here.

Sadly, around 19% of women required a second procedure as a result of complications following the initial surgery in the attempt to remove the mesh. However, the removal of this synthetic mesh can be a challenge, if not impossible, because the mesh embeds itself in the tissue and fresh tissue will grow around it. Due to the complex nature of the female anatomy in this area, full removal of pelvic mesh can require hours of surgery, which brings with it the risk of damage to the nerves and nearby organs, including the bladder and bowel.

“Sling The Mesh survey from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK) showed in 2019 that one in 20 women have attempted suicide and more than half have regular suicidal thoughts because of chronic pain, loss of sex life, constant infections and autoimmune disease.”

The complications associated with surgical mesh devices for pelvic organ prolapse and stress urinary incontinence repair are the following:

- Vaginal mesh erosion is the most common complication. Non-absorbable synthetic surgical mesh, made of polypropylene or polyester can break down or wear away over time. Part of the mesh may become exposed or protrude through the vagina

- Erosion of mesh into other organs: Less commonly, the mesh may erode into the urethra, bladder or rectum

- Vaginal mesh contraction: Shortening or tightening of the mesh over time can cause vaginal shortening, tightening and pain

- Pain during sexual intercourse

- Urinary problems

- Infections

- Bleeding

- Pelvic organ prolapse that returns

- Emotional problems.

Pelvic meshes are now banned by government bodies

The TGA approved more than 100 transvaginal mesh products for use in Australia. The first urogynaecological mesh device was accepted by the TGA for supply in 1998.

In 2016, the TGA issued an alert as to the possible complications associated with pelvic mesh implants. Similar issues have also been reported and actions taken by other international regulatory bodies.

In 2017, the TGA cancelled the approval of two specific types of urogynaecological mesh including the Uphold LITE Vaginal Support System and the Xenform Soft Tissue Repair System, both made by Boston Scientific, and the Restorelle DirectFix Anterior, made by Coloplast being used as:

- urogynaecological mesh inserted through the vagina to treat pelvic organ prolapse

- single incision mini slings used to treat stress urinary incontinence.

In 2018, the TGA cancelled the approval of all mesh devices for transvaginal placement in the treatment of pelvic organ prolapse and banned the use of single incision mini-slings to treat stress urinary incontinence.

In the US, the FDA ordered the manufacturers of these products to stop selling them in the country in 2019.

In addition, since December 2018, all mesh devices seeking application in Australia have been required to undergo a comprehensive review by the TGA. This includes detailed clinical evidence as these products belong to Class III (high risk) devices.

As of 23 June 2021, the TGA had received 899 adverse event reports related to urogynaecological mesh devices.

The first lawsuits concerning polypropylene mesh went to trial in America in 2012 and 2013.

Since then, several companies making these meshes have lost multimillion-dollar lawsuits totalling billions of dollars.

The global legal implications of the medical use of transvaginal mesh

Written by Lex Medicus Queensland State and Legal Manager, Christine Mercer

As Cristina has outlined, the history of the transvaginal mesh is shocking and should be concerning to us all, as to how this medical product was allowed to be used in mainstream medicine as a treatment for healthy women.

The stories of the women affected across the world are saddening. Many of the women struggled to even get medical advice and treatment. They weren’t believed and until the issue became part of mainstream journalism many didn’t even know that the mesh used to treat their condition was the cause. Most saw dozens of doctors before getting an explanation. Many were left suicidal. In the United Kingdom (UK), an action and support group has been created for these affected women and details the shocking stories of their symptoms and the fight for adequate treatment. They have approximately 10,000 members – Sling the Mesh.

I was working in the UK in medical negligence in 2013 when we first started seeing these cases coming through. At that point, we were aware that there were cases beginning to be brought in the United States (US) suing the manufacturers of the mesh. Unfortunately, the bringing of legal action to obtain compensation for these women was not going to be easy.

The global legal implications

Different international laws mean that reparation for patients suffering from complications resulting from their mesh have taken very different forms from country to country. I shall look at what has occurred in the UK, US and Australia.

In England, for example, cases have not succeeded when brought directly against the mesh manufacturers, as a result of the way their Consumer Protection Act, 1987 is interpreted in UK courts. For a successful action against device manufacturers under UK product liability law, the claimant has to show that the safety of the product is not such as a person is generally entitled to expect. It is the interpretation of this part of the legislation which has proven most difficult to establish in the cases.

This has meant that UK women have had to sue under the common law process for clinical negligence. The actions have had to be brought against the NHS Trusts / the surgeons that performed the procedures. This means that their cases are subject to the usual issues and difficulties, of establishing evidence of negligence, proof and the statutory time limits and an often lengthy case process in the court system. Consequently, they have to show that either the actual operation to insert the mesh device was negligently performed, or that the patient was not properly warned of the risks inherent in the mesh operation. It is on this failure to warn element that most of the claims have been brought.

The failure to warn allegations are frequently along the lines that prolapse, although distressing to many women, is not a dangerous or harmful condition, so before prolapse surgeries, surgeons should take the patient through the procedure and explore other surgical or non-surgical options and weigh the risk of having complications from the mesh against the symptoms from prolapse.

In the summer of 2020, the UK government announced it had made the decision not to provide financial compensation to women affected by vaginal mesh complications. The government said it had no plans to establish an independent redress agency and that its priority was to make medicines and devices safer. This leaves the women having to bring cases through the court system, as described above.

This announcement came following the government investigation into the mesh devices (amongst other matters) and its recommendations, completed by Broness Cumberledge in July 2020 entitled “First to Do No Harm”

Baroness Cumberlege’s report found that the mesh was inadequately tested, its use inadequately regulated and the surgeons using it often inadequately trained. She described it as a “global medical health disaster”. The report, described complaints and worries often being dismissed as “women’s problems”, leaving many traumatised, intimidated and confused. She also called for a registry of adverse complications from medical devices.

The one recommendation that has been implemented in the UK is for a network of specialist centres be set up to provide comprehensive treatment, care and advice for those affected by implanted mesh.

This has provided a practical solution to the women in terms of being able to seek funded (free) treatment and support via NHS England. The intention is that these services will bring together leading experts to provide multi-disciplinary care and treatment for all women who have experienced complications due to vaginal or abdominal mesh procedures. This includes surgeons, physicians, imaging specialists, nurses, pain specialists, physiotherapists, and clinical psychologists. Seven centres have been proposed in every NHS region. Unfortunately, they are not all as comprehensive as anticipated and the affected women still face significant waiting times to be seen.

The London Complex Mesh Centre is the most comprehensive of the centres. Their Dr Sohier Elneil states she learnt many of her surgical skills repairing injuries sustained after childbirth among teenage mothers in Africa. She has been trying to raise awareness of the mesh problems since she saw her first patient crippled by the material in 2007.

Following one of the recommendations in the Cumberlege report, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency is considering the establishment of a new regulatory framework to improve the way devices are assessed before being put on the market, and for post-market surveillance to monitor emerging problems.

In July 2018, the NHS implemented a temporary ban on the use of vaginal mesh, unless it was considered absolutely necessary. This ban was extended in March 2019.

A timeline of events: originating in the US

To understand how a product so apparently defective in what it was supposed to do, became so widely used globally we have to look back to the US.

The FDA cleared the first mesh implant to repair stress urinary incontinence Boston Scientific’s ProteGen Sling, in 1996. The first mesh for pelvic organ prolapse was approved in 2002. Despite how commonplace the use of mesh products in these procedures became following their introduction, both in the US market and globally, patients soon began to experience severe, and devastating complications.

Researchers have struggled to determine how often these issues occur, current estimates lie between 15% and 25%. What is clear however, is that when complications do arise, they are often severe and life-limiting, far more so than the original condition they were intended to treat.

In 2008, the FDA released a Public Health Notification and Additional Patient Information on serious complications associated with surgical mesh placed transvaginally to treat stress urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse. For pelvic organ prolapse in 2011, the FDA additionally noted that serious complications associated with these procedures were not rare, and that mesh surgeries did not alleviate patients’ symptoms any more than non-mesh procedures.

In 2012 the first lawsuits went to trial in America. The first major verdict came in the case of Christine Scott. Bard (the manufacturer) withdrew its Avaulta Plus vaginal mesh from the market in July 2012, weeks before losing that case with a $3.6m verdict in favour of the Plaintiff.

Johnson & Johnson lost the first federal mesh lawsuit in February 2013, with American Medical Systems becoming the first company to agree to a large settlement in July 2013. While Johnson & Johnson agreed to settle 2,000 to 3,000 lawsuits for $120 million in 2016, the company has continued to defend itself in court.

Juries in the US have concluded that the devices were defectively designed and there had been no warning about the side effects of mesh failure.

Since 2012, women who have sued the manufacturing companies have won with verdicts in US state and federal courts totalling around US$300 million. By March 2017, multiple companies had settled thousands of claims for millions.

In January 2016, the FDA reclassified urogynaecological surgical mesh. As a result, all manufacturers stopped marketing surgical mesh intended for transvaginal repair of posterior compartment prolapse.

In April 2019, the FDA ordered all manufacturers to stop sales of mesh for pelvic organ prolapse, because manufacturers could not prove the benefits outweighed the risks.

There are currently no FDA-approved surgical mesh products for transvaginal repair of pelvic organ prolapse.

The allegations

Looking at the allegations made by the women who filed the US lawsuits, it is telling as to what the cause of this global medical disaster was. They claimed that manufacturers “had a legal duty to ensure the safety and effectiveness of their pelvic mesh products” but instead provided patients with “false and misleading information” about how safe and effective the products supposedly were.

The lawsuits accuse mesh manufacturers of:

- Intentionally misleading the US FDA, the medical community, patients and the public about the true safety and effectiveness of the products.

- Failing to properly test devices.

- Failure to research the risks of the products.

- Failing to create safe and effective methods to remove the materials.

- Failing to adequately warn people of potential complications and injuries.

Around the globe, it was beginning to become clear that there had been a medical disaster for millions of women. Investigations into what had occurred were now being undertaken, as more and more women were coming forward.

In December 2017 in the UK, a review published in the British Medical Journal revealed that 61 manufacturers sold mesh without clinical trials, with safety and effectiveness evidence shown to be weak.

The estimate at that time of the number of women affected in just the UK was 100,000.

In the same month, a BBC Panorama investigation revealed that Ethicon has failed to properly warn UK doctors of the risks associated with transvaginal mesh and had inadequately tested its kits before selling them. The investigation claimed that Ethicon’s TVT-Secur implant, which had been taken off the market in 2012, had been available for commercial purchase after being tested on only 31 women for five weeks, and in sheep.

In 2020 a group of Scottish women received compensation from Johnson & Johnson for injuries caused by vaginal mesh in an out of court settlement. The claim alleging that the mesh was faulty and as a result had caused them injury. Prior to a court hearing, Johnson & Johnson’s legal representatives apparently flew to Edinburgh to discuss the settlement, and it is understood that it agreed to pay approximately £100,000 to each claimant. Johnson & Johnson were keen to stress that liability has not been admitted as part of the deal.

What is clear in looking at this chronology is the time this product was in the market and actively being used globally. We are talking a period from 1996 to initial action from the FDA in 2016 and then bans in the US in 2019 and UK in 2018. That is despite the first concerns being noted by the FDA in 2008 and 2011 and the first lawsuits being settled in the US in favour of the women, in 2012! Does that mean that for over 10 years women around the world were unnecessarily exposed to the complications and disabilities from these products?

Australia’s pelvic mesh class action

Australia has just seen the outcome of what has been described as its biggest class action, with success for hundreds of women injured by the use of mesh.

On 5 November 2021, the High Court of Australia ordered in favour of the class action for the injured women, with Justices Michelle Gordon, Jacqueline Gleeson and Patrick Keane refusing to hear Johnson & Johnson’s application for special leave to appeal the 2019 Federal Court judgment.

In November 2019, Justice Anna Katzmann of the Federal Court had found that pelvic mesh implants sold by Johnson & Johnson and Ethicon were “not fit for purpose” and of “unmerchantable quality”. Gill v Ethicon Sàrl (No 5) [2019] FCA 1905

The class action led by Shine Lawyers was brought as a product liability action. It commenced in October 2012 and culminated in a trial that ran over seven months starting in July 2017 with judgement in favour of the women. That decision was appealed by Johnson & Johnson and went before the Federal Court.

Her Honour had noted; “Although later versions [of the product] did list erosion and extrusion as potential adverse reactions, they did so in a way that was misleading or deceptive,”. “The respondents saw the commercial opportunities presented by the new devices and were keen to exploit them before their competitors beat them to it.”

It was found that Ethicon (as part of Johnson & Johnson) had sold the implants without warning women and surgeons about the risks and had rushed the products to market before proper testing.

Justice Katzmann had ruled that the three lead applicants – who represented the class were to be awarded damages of $1,276,113, $555,555 and $757,372, respectively. The Defendant was also required to pay the legal costs.

Johnson & Johnson group companies are now facing further major class and individual actions from over 11,000 Australian women. Similar class actions involving thousands of women are also underway in the US, Canada and Europe. More than 100,000 transvaginal mesh lawsuits have been filed in the US, with the manufacturer of the most commonly used meshes, Johnson & Johnson, facing the most lawsuits.

Johnson & Johnson issued a statement after the recent High Court decision stating:

“it empathises with all the women who experience medical complications.”

“Ethicon believes it acted ethically and responsibly in the research, development and supply of its transvaginal mesh products and appropriately and responsibly communicated the benefits and risks to doctors and patients in Australia”.

The future

Whilst the decision paves the way for other women to secure damages, the fight for these injured Australian women is not over. The matter will go back before the Federal Court to establish a process for determining the individual group member claims and the value of damages.

The women in all of these global claims still have to prove their damage in the same way as they would in any compensation claim – the injuries they have suffered and that those injuries were directly caused by the mesh only and their economic loss. What I have seen in other similar product actions in the UK, is that the Defendants will still make these Plaintiff’s fight for their claim for compensation. I do not envisage these cases will be any different. That means the women may still be facing a number of years before they see financial compensation.

In the UK the newly formed NHS Mesh Centres are, one would hope, at least a starting point to get these injured women the correct treatment. The problem is that the treatment is often so specialised that even the available surgeons are not experienced in it. Mesh removal is extremely complicated. One surgeon in the UK said to the BBC – has compared the removal of an implant from the pelvis to removing hair from chewing gum.

The UK Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists said in a statement: “Management of symptoms will depend on the complication and total or partial removal of the mesh may be recommended in some circumstances. Whereas for other women, mesh removal may not be the solution to the problem. Women must be informed of all options available and the benefits and risks of each so they can make the best decision about their care.”

The Scottish government has recently announced that it had awarded contracts to a hospital Missouri in the US, for women who required the surgical removal of mesh implants.

It has become clear that simple removal of the mesh is not going to be the solution for these women, it is very often not feasible and even with removal, some women are still left with debilitating injuries.

Let us hope that the global involvement of legal processes and investigations that have occurred because of the brave women who have fought in these cases, causes a change to how medical products are brought to market, that registries of device use and complications are established and overall that the commercial push of products by these massive companies is curtailed.

For more information on related transvaginal mesh implant lawsuits – click here.

********************************************************************

Some useful contacts if women require help:

Victorian mesh information and helpline

Call 1800 55 6374 (1800 55 MESH)

Peer support

Contact tvmeshsupport@whv.org.au or visit www.whv.org.au

Hospital programs

Royal Women’s Hospital phone 8345 3143

Mercy Hospital for Women phone 8458 4500

Monash Health phone 9928 8588

Western Health phone 0481 908 118