What is brain death? Implications for misdiagnosis and organ transplantation

Demonstrating brain death in a severely ill patient is a difficult task, but an essential one to determine whether an individual is qualified to receive life-saving medical care or whether any form of treatment is obsolete. This distinction is particularly relevant when a patient is a potential organ donor. In the past, cardio-respiratory death was the only definition of death, leading to errors and misdiagnosis. But nowadays the progress in our understanding of bodily functions and neurological testing have made the process of defining brain death more precise and devoid of misunderstandings. However, the assessing brain death will always be subjective by local factors including religious, societal, and cultural perspectives, regulatory requirements, and resource availability, all of which has clinical as well as legal implications.

In this article I will provide a short historical summary on the way brain death has been conceived in medicine from the 20th century and present the current criteria to assess brain death, both internationally recognised as well as practised in Australia and New Zealand.

The neurology of brain death: Historical data

In 1959, Frenchmen Mollaret and Goulon termed brain death “coma dépassé” (literally, “a state beyond coma”) which was described in 1968 as the Harvard brain death criteria. Such criteria have been revised several times since and adapted to different circumstances and jurisdictions.

The rise of intensive care medicine around the mid-1900s, firstly established during the polio outbreak in Denmark, was key to the concept of brain death. It became clear that bodies were kept alive with intensive care management independent of their brains. However, in the early 1970s pathologists noted that the brains of people who had been kept on prolonged intensive care support were “swollen, mottled grey-red, and extremely soft, at times diffluent (mushy); with autopsy, brain changes were named “respirator brain death syndrome”. Pressed under these new circumstances, in 1995 the organ donation after circulatory death was introduced.

With the onset and the growing demand for organ donation, the stringiest criteria of brain death changed, whereby organs were no longer harvested from non-heart-beating donors but from people with traumatic brain injury, cardiac arrest and brain haemorrhage, still maintaining a beating heart.

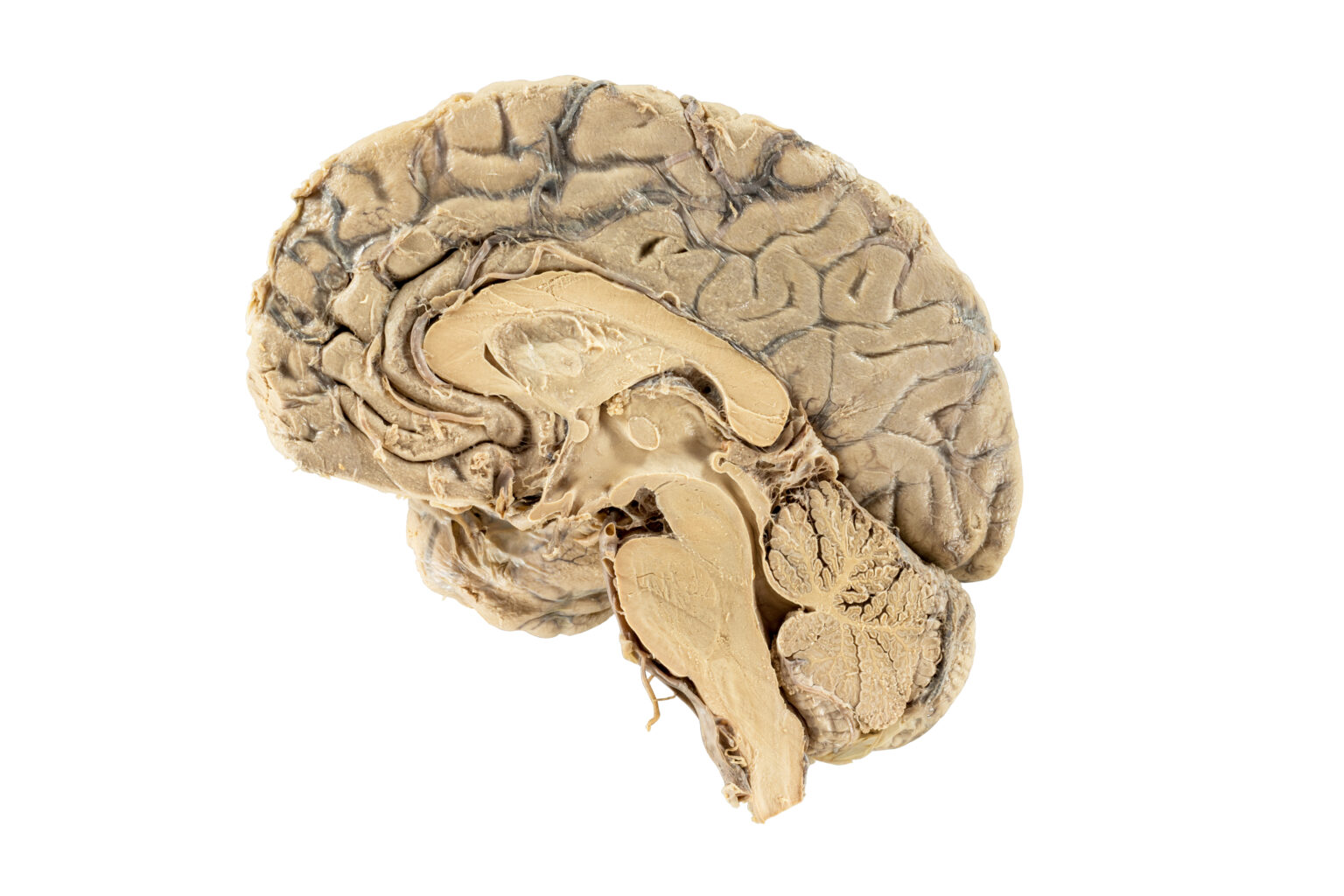

Longitudinal section of the human brain showing in the elongated lower region the brain stem (behind the cerebellum) continuing into the spinal cord

Brain death criteria according to a Danish protocol

A recent review by Dr Kindziella describes the establishment of brain death through a three-step approach, using a traffic light paradigm:

Red signifies the clinician has to pause and confirm that the prerequisites for a brain death protocol are fulfilled:

1. The unconditioned certainty that the brain disorder is irreversible and fatal, as a consequence of a known cause of brain injury. Therefore, people with an unknown cause of brain injury cannot be declared brain-dead;

2. Ensure that assessment of brain death is reliable based on physiological parameters including ruling out confounders such as administration of sedation and muscle relaxants. To exclude the influence of these drugs, clinical examination is performed 5–7 times of any drug’s elimination half-life period to make sure it is expelled from the body.

In the amber/yellow phase the clinician performs the clinical examination to:

1. Document absence of signal transmission between the brain and the spinal cord;

2. Confirm lack of brainstem reflexes;

3. Confirm the failure of hypercapnia (excess CO2 – apnoea test) to stimulate the respiratory brainstem centres.

In the final green phase, confirmatory tests may be used to corroborate the clinical examination to support absent intracranial blood flow or brain perfusion (CT angiography, transcranial Doppler, etc) and lack of electrical brain activity (EEG).

Despite the clear flow of these investigations, determining brain death remains difficult and controversial as the health conditions of the patient may not allow such tests, e.g. facial injury impairing brain stem reflexes. Other impairments include failures to adhere to the brain death protocol, (premature assessment, misinterpretation of clinical signs and confusing these signs with the processes occurring during the dying process).

A number of physiological criteria have to be ascertained and, if present, clinical testing is adapted.

Pupil dilation/restriction reflex my occur in brain death patients as a response to neurotransmitters (catecholamines) released in the bloodstream.

Brain-death-mimics may be caused by drug intoxication, or when a patient is affected by a neuro-muscular condition, like Guillen Barré syndrome. When this is recognised in combination with lack of cerebral damage by neuroimaging, the brain death protocol is halted.

Spinal motor reflexes can be present a few hours after the declaration of brain death. Because the clinical examination relies on testing the response of the brainstem, it is crucial to understand that EEG activity may arise from lingering cortical neurons firing, which may last for a few minutes to few hours after death. Even residual brain perfusion can be detected with angiography following the clinical confirmation of brain death. These factors demonstrate the complexity of the medical examination leading to the definition of brain death.

Patient receiving an electroencephalogram (EEG)

The protocols used to establish brain death vary widely from country to country. Although most countries respect the three-step approach to determining brain death, variations can be found in the timing at which repetitive testing occurs.

The interval between two clinical brain death examinations may be from one hour in Brazil, to 12 and 72 hours in Germany. In Sweden and Canada, the legislation requires one physician to perform the examination, whereas South Korea demands four physicians. In Denmark, subtraction angiography is required and in Italy and Japan EEG is mandatory. In addition, in the UK and India the concept of brain stem death has been judged sufficient as opposed to whole-brain death.

A recent review published this August 2020 in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) recognised the inconsistencies among and within countries in assessing brain death and death by neurological criteria. With this paper, the international multidisciplinary panel consisting of critical care, neurology, and neurosurgery specialists (The World Brain Death Project), formulate a consensus statement of recommendations of brain death based on the literature and expert opinion.

In a nutshell, prior to evaluating brain death, it is necessary to obtain an established neurological diagnosis of complete and irreversible loss of all brain functions, excluding all conditions potentially mimicking brain death.

Brain death criteria for medical examination

Clinical examination demonstrates coma, brainstem areflexia (absence of neurologic reflexes) and apnoea according to:

(1) No evidence of arousal or awareness to maximal external stimulation, including

noxious visual, auditory, and tactile stimulation;

(2) Pupils are fixed in a midsize or dilated position and are nonreactive to light;

(3) Corneal, oculocephalic, and oculovestibular reflexes are absent;

(4) No facial movement to noxious stimulation;

(5) Gag reflex is absent to bilateral posterior pharyngeal stimulation;

(6) Cough reflex is absent to deep tracheal suctioning;

(7) No brain-mediated motor response to noxious stimulation of the limbs;

(8) No spontaneous respiration when apnoea test targets reach pH <7.30

and PaCO2 equal or above 60mmHg.

If the clinical examination cannot be completed, supplementary testing may be considered with blood flow studies or electrophysiologic testing. Special consideration is needed for children, for persons receiving extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, and for those receiving therapeutic hypothermia (body cooling). It is further required for factors such as religious, societal, and cultural perspectives, legal requirements and resource statement.

Australia and New Zealand Statement

Under Australian law, brain death is one of two situations in which a person can be certified dead. The other is circulatory death, which is when a person’s heart stops functioning. According to the Australian New Zealand Intensive Care Society (ANZICS), the organisation I am affiliated to, determination of brain death for organ donation respects the criteria outlined in the joined statement of the Medical Royal Colleges and their Faculties in the UK.

In the document, they state: “Determination of brain death requires that there is unresponsive coma, the absence of brain-stem reflexes and the absence of respiratory centre function in the clinical setting in which these findings are irreversible. In particular, there must be definite clinical or neuroimaging evidence of acute brain pathology (e.g. traumatic brain injury, intracranial haemorrhage, hypoxic encephalopathy) consistent with the irreversible loss of neurological function”.

Sketch of the brain stem anatomy and description of brain stem death

In regard to brain stem death, the document points out that:

Brain death cannot be determined without evidence of sufficient intracranial pathology. When the brain-stem has been the primary site of injury and death of the brain-stem has occurred without death of the cerebral hemispheres (e.g. in patients with severe Guillain-Barré syndrome or isolated brain-stem injury), brain death cannot be determined when a coma and loss of all function has affected only the brain-stem, and there is still blood flow to the supratentorial part of the brain.

Thus, whole-brain death is required for the legal determination of death in Australia and New Zealand. This contrasts with the UK where brain-stem death (even in the presence of cerebral blood flow) is the standard.

Brain death in Australia is determined by clinical testing if preconditions are met, or imaging demonstrating the absence of intracranial blood flow. However, neither the clinical or the imaging tests can establish whether every brain cell has died.

The ANZICS states that there has never been a case fulfilling the preconditions and criteria of brain death to ever subsequently develop any return to brain function.

What are the preconditions to determine brain death through clinical examination?

• Sufficient intracranial pathology

• Normothermia (normal body temperature) above 35°C

• Normotension (normal blood pressure)

• Exclusion of sedative drugs (self-administered or otherwise, with blood levels below the clinical effect)

• Absence of severe electrolyte, metabolic or endocrine disturbances

• Intact neuro-muscular function tested with electromyography

• Ability to adequately examine brain stem reflexes at least by examination of one eye/ear

• Ability to perform apnoea testing (not possible in high cervical spinal cord injury or severe hypoxic failure)

Who is carrying out the clinical examination in Australia?

Clinical testing is carried out by two medical practitioners with specific experience and qualifications. It is recommended that two sets of tests be performed separately so that the doctors and the tests are seen to be truly independent. The tests may be done consecutively but not simultaneously. There is no requirement for one doctor to be present during the test performed by the other doctor, but such presence is acceptable.

All of the clinical tests, including apnoea testing, must be performed on each occasion. No fixed interval between the two clinical tests is required, except where age-related criteria apply.

The following need to be established to determine brain death by clinical testing:

• Absence of responsiveness;

• Determination of brain death;

• Absence of brain-stem reflexes;

• Apnoea.

To learn more please refer to the table on page 24 of the ANZICS Statement

The legislation regulating organ donation in Australia

All states and territories of Australia and New Zealand provide a legislative basis for the removal of tissues (including organs) after death, for the purpose of transplantation.

Legislation in the various jurisdictions uses the word ‘tissue’, which includes what health care professionals refer to as organs.

Legislation in the various jurisdictions specifies who may authorise removal of tissue and when they may authorise it, which includes the individual legal basis for the removal of tissues after death.

The designated officer. The legislation in all jurisdictions recognises a specific role within the hospital of an officer who authorises or helps with the removal of tissue for transplantation, and other therapeutic, medical or scientific purposes.

In ACT, NSW, Queensland, SA, Tasmania, Victoria and WA legislation, the role is referred to as ‘the designated officer’.

NT legislation refers to the role as ‘the person in charge of the hospital’.

ACT, SA, Tasmania, and WA legislation specifies that the designated officer must be a medical practitioner. In Tasmania legislation, the designated officer cannot be involved in the clinical care of the potential donor.

Consent to organ donation. The legislation also states that the designated officer may authorise removal of tissue if the deceased patient had expressed a wish or given consent to donation of tissue, which had not been revoked, and had not expressed an objection to donation.

Queensland legislation refers to the wish or consent as being in writing and signed; and

Victoria legislation refers to the wish or consent as being in writing at any time, or orally in the presence of two witnesses during the last illness. Objection to organ removal can occur when one or two senior next-of-kin revoke consent.

The role of the coroner. Consent for retrieval of organs for transplantation is required from the coroner. In some jurisdictions the coroner may wish to withhold consent until circulatory arrest, although conditional approval will have been given before withdrawal of treatment.

Because of the potential legal consequences in determining brain death for organ transplantation, the JAMA article concludes by providing a few recommendations, which among others include:

All countries recognise brain death as legal death. Practitioners should be protected from legal action for determining brain death. The practitioner involved in determining brain death should not be involved in organ procurement/transplantation or in the care of the transplantation recipient.

Disclaimer: All images and content published in the Lex Medicus, and Lex Medicus Publishing websites are protected by copyright.