Sport related concussion: definitions, diagnosis, management and legal implications

The Australian Institute of Sport and the Australian Medical Association published a paper in January 2017 to define sport related concussions and provide recommendations to be implemented in sport settings to reduce the incidence of concussions. The ultimate goal of the article is to define what a concussion is, and raise awareness to ensure safety and welfare of Australians participating in sport by providing the latest guidelines on concussion diagnosis, management and return to play policy.

This topic is particularly close to me as I have passionately researched traumatic brain injury for over 25 years, mostly on the severe spectrum of the condition.

Concussion and the law

The recent US$ 765 million settlement of the class action initiated by 5,000 retired football players against the National Football League has generated global coverage on the topic, raising widespread arguments from the entities involved including sports regulatory bodies and associations, colleges & schools, medical associations, research institutions, and most importantly the people suffering from neurodegenerative symptoms.

In the prominent US lawsuit, “plaintiffs accused the NFL Parties of being aware of the evidence and the risks associated with repetitive traumatic brain injuries, but failing to warn and protect players against the long-term risks, and ignoring and concealing this information from players”. In re: National Football League Players’ Concussion Injury Litigation, No. 2:12-md-02323

Epidemiological facts

In Australia, the medical profession is confronted with several challenges surrounding the impact of concussion in sport, including its definition, diagnosis, management and prevention in our country where sport is broadly practised at recreational and professional levels. Sport related concussion remains an underestimated epidemic. It has been reported that in the US alone, a range of 1.6 to 3.8 million concussions occur every year. In the US, the annual cost of sport related concussion has been calculated to be US$ 1.6 to 3.8 million.

In the Australian Football League (AFL), it is estimated that 5-6 concussions occur each season for each team, whereas in Australian Rugby (NRL), 10% of all players sustain a concussion over 1-3 seasons. In Victoria, there was an increase of 605 recorded sport related concussions from 2002 to 2010. Approximately 1 in 13 AFL players will have a concussion in each season and of that, 5 to 6 concussions occur in each team per season. In non-professional rugby, 10% of players have one or more concussions over 1 to 3 seasons.

A concussion has more detrimental effects on female brains

A concussion has more detrimental effects on female brains

Concussion in the young and female brains

In children, 1 in 5 will sustain a concussion before the age of 16 years. Teens are more prone to brain damage because their brains are still undergoing processes of plasticity and myelination until they are 25 years old. Thus, any head injuries may potentially alter brain development. The way we assess concussion in children and teenagers differs from adult concussions. The identification of concussion in kids is made more difficult as parents often do not report symptoms to health professionals.

Interestingly, females experience higher rates of concussions and suffer from more severe symptoms. Females are also twice as likely to have ongoing cognitive and balance issues following a concussion. The reasons behind this vulnerability are not known, with speculations existing around a weaker neck strength, neuroanatomical differences to the male brain, hormonal influence on the brain but also the evidence that women tend to report a sport related concussion more easily than men do. The lack of understanding on the effects of concussion in females may also relate to a study bias as most research focuses on male subjects.

What is a concussion?

A concussion is a less severe form of mild traumatic brain injury. It is the result of low-velocity impact shaking the brain within the skull. The impact can be direct to the head or indirect (e.g. whiplash), whereby the impulsive force applied anywhere in the body is transmitted to the head.

The outcome from a concussion can differ based upon the type of forces hitting the head. In fact, studies using specific devices mounted on helmets of contact sport players have helped to determine that rotational and angular forces are more dangerous as they cause the brain to twist around the brain stem, the elongated portion of the brain connecting to the spinal cord. Such trauma is more likely to lead to loss of consciousness. However, loss of consciousness is not required for a person to be concussed. In fact, as we will observe later, there is an array of recognised symptoms resulting from a concussion that is sufficient for the diagnosis.

The axon is the long fibre of a neuron responsible for the conduction of the electrical impulse between neurons. Axons are covered by the fatty myelin sheath. Inside the axon are several parallel filaments that can be stretched and damaged by forces causing a concussion.

A concussion is not only a functional disturbance, but it does alter brain structures

Until recently, a concussion has been defined as a mere transient functional neurological disturbance in the absence of physical changes in the brain. However, new research utilising high-definition imaging techniques has revealed subtle structural alterations within the white matter of the brain, namely the area that is rich of neural filaments, or axons, which are covered by the myelin sheath. When axons are stretched as a result of a concussive force, it causes a disruption of the small microtubular filaments that run parallel within the axons, impairing the propagation of neural signal between neurons and also reducing the connection between brain regions. Concomitant to these changes is reduced blood flow, energy failure, increased permeability of the brain vasculature, and neuroinflammation. Clearly, at this altered physiological phase the brain is particularly exposed to further damage.

A subconcussion is a mild hit, below the concussion threshold, not translating into clinical symptoms. In contact sports, it may occur during tackles, collisions, and headers. Players are usually unaware of the impact and remain in the game without notice. However, repeated subconcussions over a sport season or throughout a professional sport career can lead to cumulative brain changes, which have been alleged to be the main cause of neurodegenerative conditions often manifesting years to decades after retirement from sport.

A second impact syndrome is the event of a second concussion, usually less severe, soon after a first concussion. A second impact can have additive or even synergistic consequences on brain damage, as it occurs when the brain is at its most vulnerable phase while recovering from the first concussion. The outcome can be detrimental as it prolongs recovery.

A post-concussive syndrome refers to the protraction of clinical symptoms for weeks to months after a concussion. It can be the result of a severe concussion or following repetitive concussions.

Following an initial concussion, brain metabolism is altered, and a second impact is sufficient to precipitate the vascular as well as the biochemical and neurological responses. Enhanced physiological dysfunction caused by a second impact may lead to severe brain swelling (oedema), morbidity and in some cases even death. It is well established that the risk of concussion triples with a previous concussion and is a particularly higher risk in aggressive players.

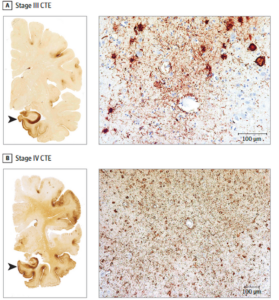

Staging of the severity of CTE has been proposed by researchers of the Boston group.

Shown here is the abundant deposition of Tau protein in a brain diagnosed with severe CTE.

The discovery of chronic traumatic encephalopathy CTE

The neurological condition caused by repetitive concussions was reported in 2005 by a neuropathologist, Dr Omalu, who observed dramatic changes in post-mortem brain of a professional football player who sustained multiple concussions over his career. The condition was defined chronic traumatic encephalopathy or CTE. CTE is a neurodegenerative disease that develops over years or decades following the effects of multiple head traumas. In the 1970s it was known as dementia pugilistica as defined pathologically in older boxers.

The association between brain injury and CTE first arose in the US when several retired football players claimed to have developed a premature cognitive decline, behavioural changes and depression that led to their suicide. Some of these sportsmen donated their brains to research laboratories in the hope of elucidating the pathophysiology of their condition and help their peers to avoid suffering the same fate.

Although a concussion does not show any structural changes on a routine magnetic resonance scan, post-mortem microscopic analysis reveals profound atrophy of brain tissue, global activation of inflammatory cells and deposition of pathological proteins (phosphorylated tau) in a pattern “similar” to Alzheimer’s brains. Although controversies remain about the impact of concussion on the development of CTE, most scientists believe it to be a true phenomenon. The risk factors for CTE are the age of first exposure to contact sport, the number of concussions, the severity of brain injuries, the number of years playing, the mechanisms of injury (linear vs rotational acceleration) and pre-existing neurological conditions that may overlap with CTE. Despite the evidence, CTE remains controversial and its incidence unknown.

The diagnosis of CTE in Australian footballers

In Australia CTE was first identified in a former AFL player, Barry “Tizza” Taylor, who died in 2014, and whose brain tissue was diagnosed with severe CTE by the Boston group in 2017. More recently, CTE was also confirmed in the brains of Graham Polly Farmer who died after many years of suffering from dementia and Danny Frawley who has been afflicted by mental health issues.

Likewise, former Richmond player Shane Tuck was diagnosed with the most severe form of CTE after he took his life at only 38 years of age in July 2020. Tuck played 173 AFL games over 10 years from 2004 to 2014. Besides football, in the last years of his sporting career, Tuck was a professional boxer from 2015 to 2017. A Coroners Court investigation has been undertaken to clarify the association of the head impacts sustained in both sports and the development of CTE.

In order to improve our understanding of the incidence of CTE, the AFL has been urged by the Coroner to encourage players to donate their brains for research. The AFL Players Association is actively cooperating with The Australian Sports Brain Bank in NSW (where Tuck’s brain was diagnosed with CTE) concerning continued research on CTE in AFL players.

In regards to Tuck’s case, last January the AFL spokesman emphasised the commitment of the sport to review and change the game laws to reduce high contacts during the game and use the ARC (the league review hub) to identify potential concussive impacts using video technology. Last month, it was revealed that the AFL is considering creating a $2 billion concussion trust fund to support past, present and players suffering from the long-term effects of sport related concussion.

Symptoms of a sport related concussion

A concussion is associated with a variety of neurological symptoms, which usually resolve spontaneously over 7-10 days. The onset of such symptoms can manifest immediately after an impact or arise over 24-48 hours, with no clear association or memory of a traumatic event. Symptoms include loss of consciousness (only in 10% of concussions), headache, confusion, amnesia, vision disturbance, sensitivity to light, poor balance, sleep changes, dizziness, irritability, cloudy brain and more. Once a concussion has been diagnosed, the player remains under 24-hour observation leading to admission to Emergency if symptoms worsen when escalating into seizures, increasing headache, loss of consciousness and vomiting.

Diagnosis of a sport related concussion

The diagnosis and initial management of a concussion are at best achieved at the sideline. This is the first approach to identify a suspected concussion. In such cases, protection of the cervical spine is also recommended until any neck injuries have been excluded.

The Concussion Recognition Tool 5 is a single page questionnaire used by non-medical staff to detect a possible concussion at the sideline.

The assessment can be performed by a person without medical training using the Concussion Recognition Tool 5, a simple collection of different signs and symptoms ranging from “Red flags” (neck pain, double vision, severe headache, seizures, loss of consciousness, vomiting, increasing restlessness, etc), as well as observable signs, symptoms, and memory assessment. Once a concussion is suspected, the player is removed from the game, monitored for 24 hours and not allowed to return to activity until further assessment regardless of resolution of symptoms. It also provides a set of rules of what not to do immediately after a concussion: not to leave the athlete alone, not to consume alcohol and not to drive a motor vehicle.

The Sport Concussion Assessment Tool 5 is only used by medical professionals and includes 8 pages of athletes background information, symptoms and signs required for the diagnosis of a sport related concussion.

The Sport Concussion Assessment Tool 5th Edition is a more complex questionnaire only to be used by medical professionals. This latest version of the SCAT-5 was compiled at the 5th International Consensus in Sport in Berlin in 2016. This convention saw the participation of experts in traumatic brain injury, dementia, imaging and brain injury biomarkers. The SCAT-5 questionnaire is divided into eight sections including athletes’ background information,

- “Red flags” as per above,

- Observable signs (facial injuries, motionless, balance, disorientation),

- Memory assessment,

- Consciousness,

- Cervical spine assessment,

- Symptom’s evaluation (headache, dizziness, nausea, confusion, anxiety, etc),

- Cognitive screening (orientation, immediate memory concentration)

- Neurological screen which ends in the final decision.

Upon recognition of a concussion, the player is removed and is not to return to play until reassessed. Assessment of concussion in children is achieved with a slightly modified SCAT-5 questionnaire, the Child SCAT-5, requiring the participation of the parents.

Unfortunately, there are no other means that help the diagnosis of a concussion. Intensive research in this area is rapidly expanding with the scope to develop biomarkers of brain damage and more sensitive magnetic resonance technology that may detect subtle structural brain changes for a definitive detection of a sport related concussion.

Prognosis and return to play policy

The resolution of concussion symptoms varies and depends on the concussion severity, persistence of the symptoms and medical judgement. Given the vulnerability of the child/adolescent brain as well as female brains, criteria vary substantially. The standard protocol suggests a rest of two weeks in adults and four weeks in teenagers, which is sufficient for recovery in 80% people. In a small, yet significant proportion of players, around 10-15% recover only after months and are affected by post-concussive syndrome. In 5%, symptoms persist indefinitely.

During the rehabilitation period it is critical to avoid contact sports. Light aerobic exercise (no contact activity) can resume if symptoms are not elicited or aggravated. Meanwhile, the Cocoon therapy or strict brain rest (physically & mentally) has been found to be rather detrimental, being replaced with active rehabilitation programs to improve recovery. Sadly, no pharmacological treatments are available for concussion symptoms.

How return to play works

Return to sport protocol included in the Concussion in Sport Australia Position Statement requires the player to be symptom-free for at least 24-48 hours before light anaerobic activity can resume. The rehabilitation protocol continues with a gradual increase in physical demand prior to a full return to contact sport. However, with the reappearance of the symptoms the player will be tested again and set back in the lower rehabilitation stage of the program.

Return to sport protocol to be followed after a concussion in adults over 18 years. In green is the slight modification required for children with a longer return to play period of 14 days from complete symptom resolution compared to 24-48 hours in adults.

It is accepted that upon diagnosis, a child should not return to play prior to 14 days from complete resolution of all concussion symptoms. To give the brain a chance to heal, not only physical activity but also cognitive tasks at work and school should be suspended and resumed gradually.

The inclined treadmill is used for the Buffalo concussion treadmill test for diagnosis and recovery after a concussion

The autonomic nervous system for diagnosis and recovery after a concussion

There is an additional approach to diagnose and rehabilitate a concussed player. New research has recognised that a concussion deeply influences the autonomic nervous system, which regulates the cardiovascular (sympathetic nervous system) and peripheral vasculature (parasympathetic nervous system). The functions controlled by the autonomic nervous system that are assessed after a concussion relates to changes in heart rate, pupillary reflex, vestibulo-oculomotor function and arterial pulse. These parameters are measured while the patient is challenged with increasing physical activity, for example using the Buffalo Concussion Treadmill Test (a treadmill with increasing incline). When the heart rate and blood pressure show abnormal function, the test is stopped. This approach to concussion assessment is more sensitive to detect subtle symptoms, of which the player is unaware. These alterations can last for several weeks. The treadmill test is also very helpful in recovery training.

Education in preventing sport related concussion

Increasing the awareness of concussion in sport by informing players, coaches, teachers, parents and children/adolescents is of paramount importance. Certain sports practices and specific roles within a team clearly increase the risk of a concussion. A lawsuit from 2016 by student athletes against the American National Collegiate Athletic Association led to a settlement of US$ 75 million in 2016, whereby US$ 70 million will be used for a medical monitoring program for college athletes and a US$ 5 million invested in a program “to research the prevention, treatment, and/or effects of concussions.” This includes a broad educational program for an estimated 4.4 million students.

Implications in Australia

There is intense debate on prevention of concussions in Australian sport. In the event of a sport related head trauma, many interests are at stake, which may result in denial of the occurrence of a concussion during a game. A player may understate their symptoms to continue participating in an important game; a coach may not want to risk the success of a game by removing a pivotal player from the field; a team doctor may feel an overwhelming responsibility in deciding to stop a player from the game. The pressure on all team members is strong and poses a risk on the player’s wellbeing. The precedent of the large lawsuit settlement in the US has positively contributed to instating many precautions aimed to:

- inform all team members on the characteristic symptoms of a concussion

- introduce internationally recognised diagnostic tools (SCAT5)

- assess players who have sustained a hit on the head to ascertain whether they have been concussed

Lastly, remove players when a concussion is suspected based on the principle: If in doubt, sit them out.