Defining pain

Pain is defined by the International Association for the Study of Pain as “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with, actual or potential tissue damage”.

There are two broad categories of pain – (i) acute pain, which occurs with trauma and usually gradually resolves, and (ii) chronic pain, which by definition is pain that persists for more than 3 months.

There is a further variety of pain known as neuropathic pain which is primarily caused by injuries to nerves themselves. This pain typically has specific features of burning, electric shock-like sensations, tingling and shooting components.

The anatomical pathways involved in processing pain are illustrated in the figure. The pathway comprises a series of nerve cells which are specifically linked to process the painful stimulus.

A-delta fibres signal initial pain, C lasting pain. The pain stimulus travels to the dorsal horn of the spinal cord to the brain region, thalamus, where it is transferred to the cortex. In the thalamus, the pain stimulus is transformed into perception and releases hormones to suppress pain. Somatosensory cortex helps localise pain and processes it into consciousness. Generally, ascending pathways process the sensation of pain; descending pathways modulate the sensation of pain.

Chronic pain

Chronic pain may be due to a continuing source of activation of pain receptors in the periphery (nociceptors) such as arthritis, or more commonly to excessive activation of the pain nerve pathways which conduct the pain impulses from the periphery to the brain (see below). This process of amplification of the pain signals in the spinal cord and brain causing chronic pain is known as central sensitisation. It is due to a range of neurochemical and electrical alterations in the spinal cord and brain, such that the pain nerves fire at a faster rate than normal and send incorrect messages to the conscious brain about the severity of pain. These mechanisms have been extensively documented in animal models of chronic pain as well as in humans.

It is thought that this process of central sensitisation is responsible for a lot of the pain experienced by patients with whiplash, fibromyalgia, chronic musculoskeletal pain, migraine headaches, temporomandibular joint dysfunction, and a range of other disorders.

Our conscious perception of chronic pain is not simply a function of the activity of the pain nerves themselves. An important complicating factor in how we experience chronic pain is the individual’s emotional and behavioural response to pain. These psychological factors have a major impact on whether we perceive chronic pain as being a mild annoyance or an extreme imposition which may consume a person’s life. Thus, at the same theoretical level of pain nerve activity, two individuals may have diametrically opposed reactions to chronic pain. It generally appears that people who are depressed, who perceive adversity or illness as more serious than it actually is (catastrophisers), and those who have had severely traumatic psychological or physical experiences early in life tend to have more extreme emotional reactions to pain. Chronic pain is therefore perceived differently from person to person which may also depend on gender, age, cultural background, socioeconomic factors and pre-existing conditions.

The treatment of chronic pain is difficult and diagnostic methods and strategies of pain treatment are not always successful. To make matters worse, chronic pain is often neglected by the health care provider because it is too difficult to treat or by the patient themselves. For these reasons, chronic pain is a widespread medical problem with major implications for the medico-legal sector.

The cost

It was reported in 2012 that one in five adults suffers from chronic pain in Australia. This involves a significant monetary cost for healthcare and the society at large reaching over AU$ 55 billion in that year for musculoskeletal pain alone. Of this, the direct cost, encompassing the actual medical diagnostics and care reached over AU$ 9 billion. The indirect cost, referring to loss in productivity, had even a higher burden of AU$ 20 billion, while loss in quality of life amounted to AU$ 34 billion.

How to address pain

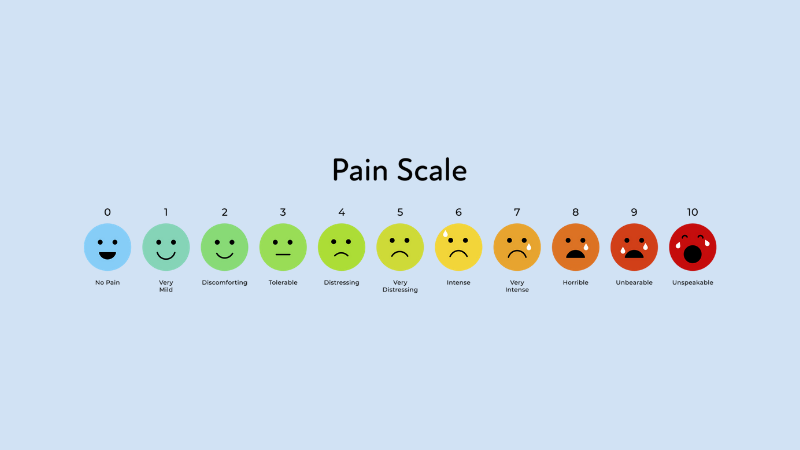

Due to its individual nature, there is no easy way to measure another person’s level of pain. Therefore, it is paramount to assess a person’s pain in the general context of their general health, employment and socio-economic status in order to determine the most appropriate treatments.

Acute or nociceptive pain, when mild, can be treated with simple analgesics such as paracetamol, aspirin and anti-inflammatory drugs.

Moderate pain can be addressed with the above and milder opiate type medications such as codeine and tramadol.

Severe pain, generated by a bone fracture or surgery, requires treatment with opiate drugs such as morphine, oxycodone, and fentanyl which bind to opioid receptors mostly located in the brain. These receptors normally function to process the naturally produced hormones, called endorphins. These drugs have limitations and must be used with care because of their powerful addiction potential. Widespread use of oral opiate medications for pain has been associated with a recent epidemic of opiate drug abuse with major social and societal implications.

Neuropathic pain is the consequence of nerve damage. Interestingly, drugs used for the treatment of epilepsy are the first option to treat neuropathic pain such as pregabalin, gabapentin, carbamazepine as well as certain antidepressants such as amitriptyline and duloxetine which have specific effects on pain nerve pathways.

In chronic pain, the above medications are used but with variable success. A major component of managing chronic pain is to help the affected patient learn to deal with their pain and to encourage resumption of normal function despite the pain. This is the aim of pain management clinics.

Pain and depression

There is a powerful link between pain and depression. Patients suffering from prolonged pain become depressed; in turn, depressed individuals have a higher risk of chronic pain. That these conditions are strongly related is supported by the effective treatment of chronic pain with anti-depressants.

This brief summary clearly indicates that more attention to chronic pain is required to address the condition. Patients suffering from chronic pain are treated at best in specialised pain management clinics that operate in a multidisciplinary approach to encompass pain specialists, physiotherapists, occupational health professionals, social workers and psychologists/psychiatrists. With an early, holistic intervention aimed at breaking the circuit of chronic pain, we may help patients to achieve a better quality of life, early reintegration to work and reduce medical costs.

About Dr Peter Blombery

Consultant Physician, Dr Peter Blombery is an accredited Independent Medical Examiner with a key interest in the assessment of cardiovascular disease & pain disorders, particularly complex regional pain syndrome & chronic neuropathic pain.

See Dr Blombery’s full medico-legal expert profile here.