The progress of medicine goes parallel to the increasing availability of diagnostic tests that help a physician to navigate through a suspected condition in symptomatic patients, as it happens when someone with chest pain is prescribed an electrocardiogram to ascertain for a possible myocardial infarct.

Additionally, diagnostic tests represent valuable means for disease prognosis by allowing to monitor disease progression as well as for assessing the efficacy of a treatment.

Diagnostic tests have also become a critical approach to screen for disease in asymptomatic patients, mostly aiming at early detection of cancers such as cervical cancer (Papanicolaou, PAP test), breast cancer (mammogram), colon cancer (colonoscopy), and prostate cancer (blood levels of prostate specific antigen, or PSA).

Despite the improved specificity and sensitivity of diagnostic tests, their more frequent employment can become a problem. Overuse of unneeded services can harm patients physically and psychologically, and proves detrimental to health systems. Excessive expenditure leads to wasted resources and deflects investments in both public health and social spending. Although the damages from testing overuse have not been properly quantified and well described, overuse is likely to be increasing worldwide in both high- and low-income countries.

There are relevant definitions to truly understand the problem at the core of overtesting.

Overuse: ‘the provision of medical services for which the potential for harm exceeds the potential for benefit’. Unfortunately, overuse cannot be objectively measured as it has not been well characterised, making the problem to establish adequate testing and treatment quite difficult to overcome.

Overdiagnosis: the diagnostic labelling of abnormalities or symptoms that are indolent, stationary, and will not cause considerable distress or shorten the person’s life.

Overtreatment and overtesting indicate the inappropriate delivery of particular types of services.

Due to the improvement in diagnostic testing and changes to screening guidelines, medical testing continues to evolve in both ways; for the benefit of patients as well as the delivery of unnecessary treatments.

In regard to cervical cancer screening, the small risk of overdiagnosis and subsequent overtreatment are outweighed by the reduction in risk of death, thus making this screening beneficial to our female population.

Conversely, the case of overdiagnosis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children resulting in overtreatment, can negatively impact on a child’s self-esteem and ability to modulate own behaviour and peer interaction.

Overdiagnosis also applies when the definition of disease is broadened, leading to populations that were previously considered healthy being labelled as ill. For instance, lowering risk thresholds for the treatment of elevated cholesterol resulted in increased populations receiving statins (cholesterol-lowering drugs), with dubious benefit.

Futility, harm and cost are closely related. Although some diagnostic tests are quite harmless, others are significantly invasive such as venography, a procedure to assess vein thrombosis that brings along a series of potential complications. Some of these can be quite serious, as compared to alternative venous duplex ultrasound.

There is also a significant difference in the relative cost of each procedure, which adds to the national expenditure for health care. Therefore, wise scrutiny on the true necessity in running specific diagnostic tests has become a priority to achieve the optimal balance between the benefits to patients and the potential adverse effects, time involved, and money wasted.

The pressures are many in regard to overtesting. A patient feels reassured and heard if the treating doctor will prescribe diagnostic tests to find out what concerns him/her; conversely, the doctor may play “defensive medicine” for not offering testing in fear of being sued for malpractice and thus minimise the risk of a lawsuit.

The money issue

The elephant in the room is, of course, money. Some physicians have a direct financial conflict of interest in making decisions on the services provided to patients. Those health care providers who own surgical, laboratory, or radiological clinics receive extra compensation from the services they offer to their patients.

A recent survey cited in a commentary of the Journal of the American Medical Association found that over 70% of physicians believe that they are more likely to perform unnecessary procedures when they profit from them.

International initiatives to rationalise medical testing to reduce risks, cost and improve patient benefit

The problem of low-value medical care has become substantial for high–income countries and increasingly also in low-income countries. Some international initiatives have been established with the scope to raise awareness in both physicians and the public, to identify a list of tests and procedures that may have low relevance for the patients’ benefit.

One such initiative is Choosing Wisely, launched in 2012 in the US to promote conversations between clinicians and patients by helping patients choose care that is:

- Supported by evidence;

- Not duplicative of other tests or procedures already received;

- Free from harm;

- Truly necessary

National medical societies have asked their members to identify tests or procedures commonly used in their field whose necessity should be questioned and discussed. This has resulted in speciality-specific lists of “Things Providers and Patients Should Question”.

Some experts estimate that in the US at least $200 billion is wasted annually on excessive testing and treatment. This overly aggressive care can also harm patients, generating mistakes and injuries believed to cause 30,000 deaths each year.

Initially, the Choosing Wisely initiative focused on cutting the number of elective caesarean sections, reducing opioid use and avoiding overtreatment for patients suffering low-back pain. Only a year from the implementation of the Choosing Wisely guidelines, one hospital (Cedars-Sinai) avoided $6 million in medical spending.

However, Dr Richard Sun, the co-chairman of the Smart Care group initiative in California, stated, “one challenge is developing metrics that everyone can agree upon to measure improvement”.

The equivalent initiative in the UK is NICE, (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence), compiling a “do not do” list, to provide national guidance and advice to improve health and social care. Ultimately, NICE’s role is to improve outcomes for people using the NHS and other public health and social care services.

They do this by:

- Producing evidence-based guidance and advice for health, public health and social care practitioners.

- Developing quality standards and performance metrics for those providing and commissioning health, public health and social care services.

- Providing a range of information services for commissioners, practitioners and managers across health and social care.

Such guidelines make evidence-based recommendations on a wide range of topics. These include preventing and managing specific conditions to planning broader services and interventions to improve the health of communities. They aim to promote integrated care where appropriate.

These guidelines address the following:

- Antimicrobial prescribing guidelines;

- Interventional procedures;

- Medical technologies guidance;

- Diagnostic guidance;

- Technologies appraisals guidance;

- Highly specialised technologies guidance.

The Australian Comprehensive Management Framework for the MBS (CMF)

In the 2009 – 10 Budget, the Australian Government announced funding over two years to develop a new evidence-based MBS Quality Framework — subsequently named the Comprehensive Management Framework (CMF) for the MBS (Medical Benefit Scheme). Consistent with international efforts, CMF sought to improve transparency and provide a stronger evidence base for services listed on the MBS to maximise health outcomes and efficiency.

The CMF set out to establish and ensure that prospective and already listed items:

- Meet agreed standards for effectiveness and safety.

- Are likely to lead to improved health outcomes for patients.

- Represent value for money.

The published research by Australian authors includes the literature database of over 5000 international studies, where they identified 156 potentially ineffective or unsafe (non-pharmaceutical) services to be flagged for consideration. Among those services are these 13:

- Testing of patients for factor V Leiden gene mutation.

- Arthroscopic surgery for knee osteoarthritis.

- Testing for C-reactive protein.

- Chest X-ray for acute coronary syndrome, preoperatively, or in diagnosing respiratory infections.

- Chlamydia screening.

- Exercise electrocardiogram (ECG) for angina.

- Imaging in low back pain.

- Liver function tests.

- Blood, urine or plasma testing in end-stage renal disease.

- Radical prostatectomy.

- Radiotherapy for patients with metastatic spinal cord disease.

- Routine dilatation and curettage.

- Surgery for obstructive sleep apnoea.

The authors of this literature search conclude that “research must indicate the populations most likely to benefit from or be harmed by services, thus allowing the development of effective policies for refining the indications for coverage and minimising use outside these indications.

How this is achieved in various systems will differ: fee-for-service systems might require tighter clinical item and patient descriptors and fee refinements, whereas program budget, bundled or capitated systems can introduce incentives for optimal use of services that offer the best patient outcomes”.

Unnecessary and overuse of radiological testing for low back pain

Internationally accepted medical guidelines are extremely clear and supported by studies demonstrating that routine imaging for low back pain does not lead to improved pain, function, or quality of life. The radiological tests are not only a waste of time and money, but unnecessary imaging may prove seriously harmful.

Despite the scientific evidence, in the US between 1995 and 2015, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and other high-tech scans for low back pain increased by 50%, and up to 35% of those scans were considered to be inappropriate.

The review concluded that inappropriate imaging is common in low back pain management, paradoxically leading to both overuse where imaging is not indicated and underuse when it is indicated.

Unnecessary imaging is not only confined to just low back pain. Americans spend more than $100 billion on various types of diagnostic imaging each year, much of which is unnecessary and potentially even harmful.

Overuse of diagnostic imaging has been evident over several years, but it is well recognised that medical practice is reluctant to changes. Common understanding suggests that, on average, it takes 17 years for new medical knowledge to be incorporated into practice.

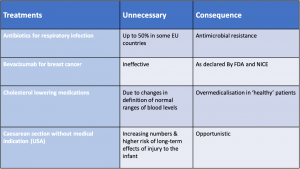

Table 1. Evidence for inappropriate care

Table 2. Indirect evidence of excessive care

These tables summarise data reported in the publications cited in this article where outcomes are defined in a different manner, either as a percentage of unnecessary/inappropriate test/treatment in specific countries or highlighting the detrimental consequences for the patient.

Cancer screening programs in Australia

In Australia, there are three government-funded population-based screening programs – the national breast cancer screening program (BreastScreen Australia), the National Cervical Screening Program (NCSP), and the National Bowel Cancer Screening Program (NBCSP). Options for early detection of other cancers (e.g. hepatocellular carcinoma and melanoma) are under investigation.

What are the health benefits, harms and cost-effectiveness of population-level for these programs also including targeted-risk screening for lung cancer and Lynch syndrome, and prostate specific antigen (PSA) testing?

Breast cancer

BreastScreen Australia was phased in from 1991, providing free biennial mammographic screening among women currently between 50 and 74 years of age. An independent evaluation published 10 years ago concluded that this program had reduced mortality from breast cancer in women aged 50–69 years by approximately 21–28%. Additionally, early detection reduced the intensity of treatment. However, the study detected a proportion of overdiagnosed and thus overtreated breast cancers, as for the case of ductal carcinoma in situ, which does not progress in metastatic cancer in 26-60% of women. Surveillance instead of radical mastectomy would be recommended.

Cervical cancer

Cervical cancer screening via the Papanicolaou test for women aged 18–69 years reduced mortality by half over the period of 1991–2018, from 3.8 to 1.8/100 000 women.

In women, the screening and incidence of cervical cancer has had a significant ground-breaking change thanks to the National HPV Vaccination Program introduced in 2007 for girls aged 12–13 years. The HPV related cancers are over 70% cervical cancers. The transition from a biennial cell-related testing to a five-yearly HPV-genomic specific testing in combination with the efficient HPV vaccination program is estimated to prevent 587 deaths over the period 2018–2035.

Colorectal cancer

Changes in the current guidelines have drastically reduced the number of relatively invasive and not risk-free colonoscopies as a preventative measure to detect early colorectal cancers. This change was introduced in 2019 with biennial screening using immunochemical faecal occult blood testing (iFOBT) to people aged 50–74 years. iFOBT is estimated to prevent 97 000 colorectal cancers and 57 100 deaths in 2020–2040 at the observed ~40% participation rate, equivalent to more than 4000 colorectal cancers and more than 2500 colorectal cancer deaths prevented annually. This new screening program provides the most favourable cost-effectiveness and benefits-to-harms ratios, which is bound to reduce the high cost predicted to top $2 billion by 2040 without screening.

Prostate “specific” antigen

PSA remains the only molecular test for prostate cancer screening, but the specificity of this test remains inconsistent. Approximately 1.5 million PSA tests in Australia were subsidised by Medicare in 2017. Although a European study reported a 21% reduction in prostate cancer mortality in men aged 55–69 years who underwent PSA testing every 4 years, a systematic review and meta-analysis based on five trials on PSA testing concluded that PSA testing may have no effect on prostate-specific mortality.

An Australian study that evaluated the cost-effectiveness of 4-yearly PSA testing versus no testing for men at average risk, high risk and very high risk for prostate cancer found that annual PSA testing may be cost-effective for very high–risk men, but not for average-risk or high-risk men.

However, to date, the inaccuracy of PSA testing as a screening tool prevents the assessment of meaningful cost-effectiveness analyses at a population level. Morbidity associated with treatment remains a significant problem. More research is needed to develop alternative and more reliable screening tests to identify prostate cancer and guide physicians toward appropriate therapies.

End of life care

Overuse of aggressive care for dying patients and underuse of palliative care remains a sensitive issue. Inappropriately aggressive cancer care near the end of life has been identified as a common problem in Canada, the USA and the UK, with regional variations observed. Overuse of aggressive end-of-life care in the UK, for example, includes futile insertion of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tubes and administration of chemotherapy, radiotherapy or useless medications like statins, that hasten death.